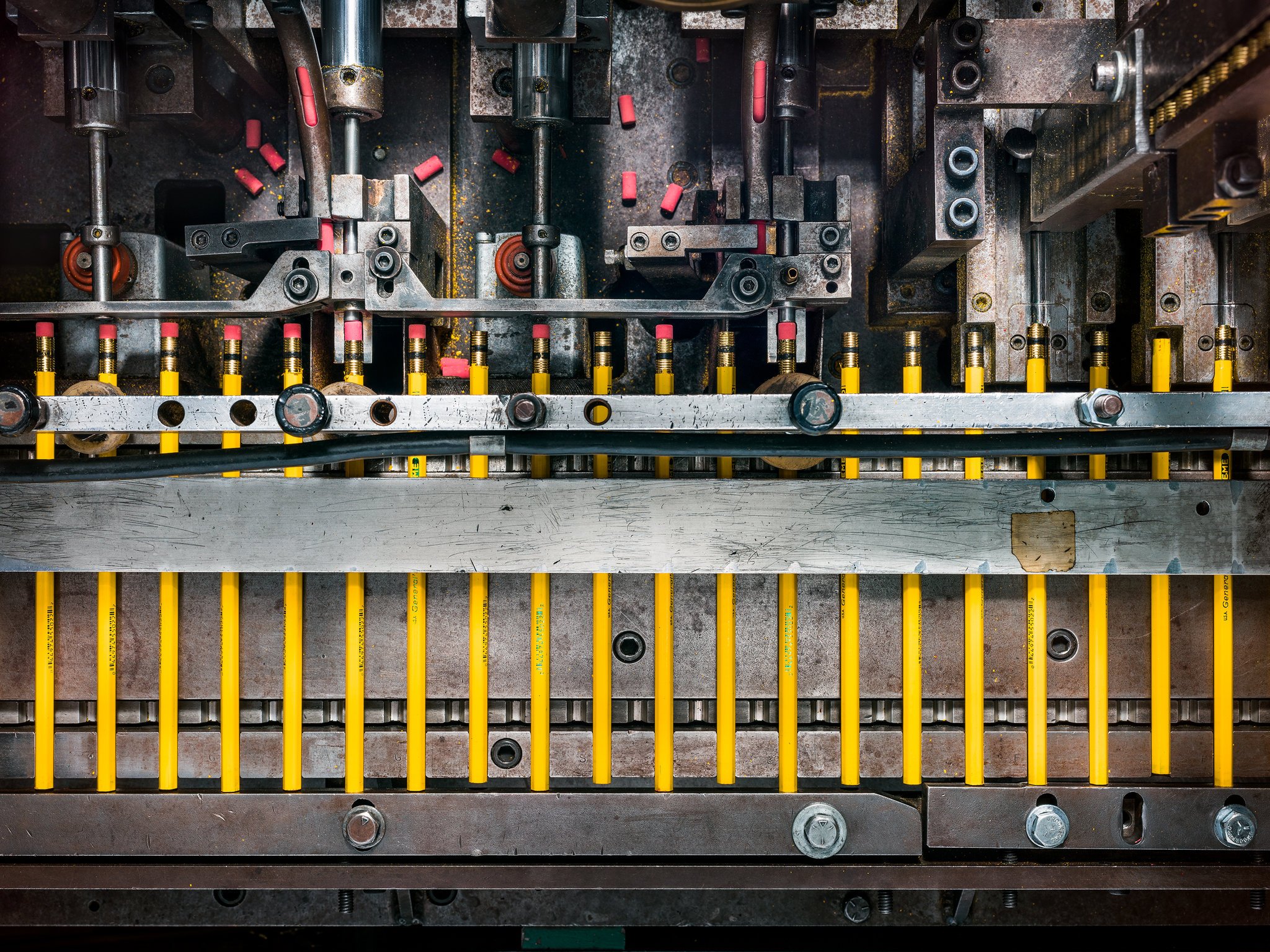

The tipping machine adds metal ferrules and erasers.

After receiving a coating of paint, pencils are returned by conveyor for another layer. Most pencils receive four coats of paint.

On some pencils, a capper installs smooth metal caps — no eraser.

Pencils are sharpened by rolling them across a high-speed sanding belt.

Over the past few years, the photographer Christopher Payne visited the factory dozens of times, documenting every phase of the manufacturing process. His photographs capture the many different worlds hidden inside the complex’s plain brick exterior. The basement, where workers process charcoal, is a universe of absolute gray: gray shirts, gray hands, gray machines swallowing gray ingredients. A surprising amount of the work is done manually; it can take employees multiple days off to get their hands fully clean. Pencil cores emerge from the machines like fresh pasta, smooth and wet, ready to be cut into different lengths and dried before going into their wooden shells.

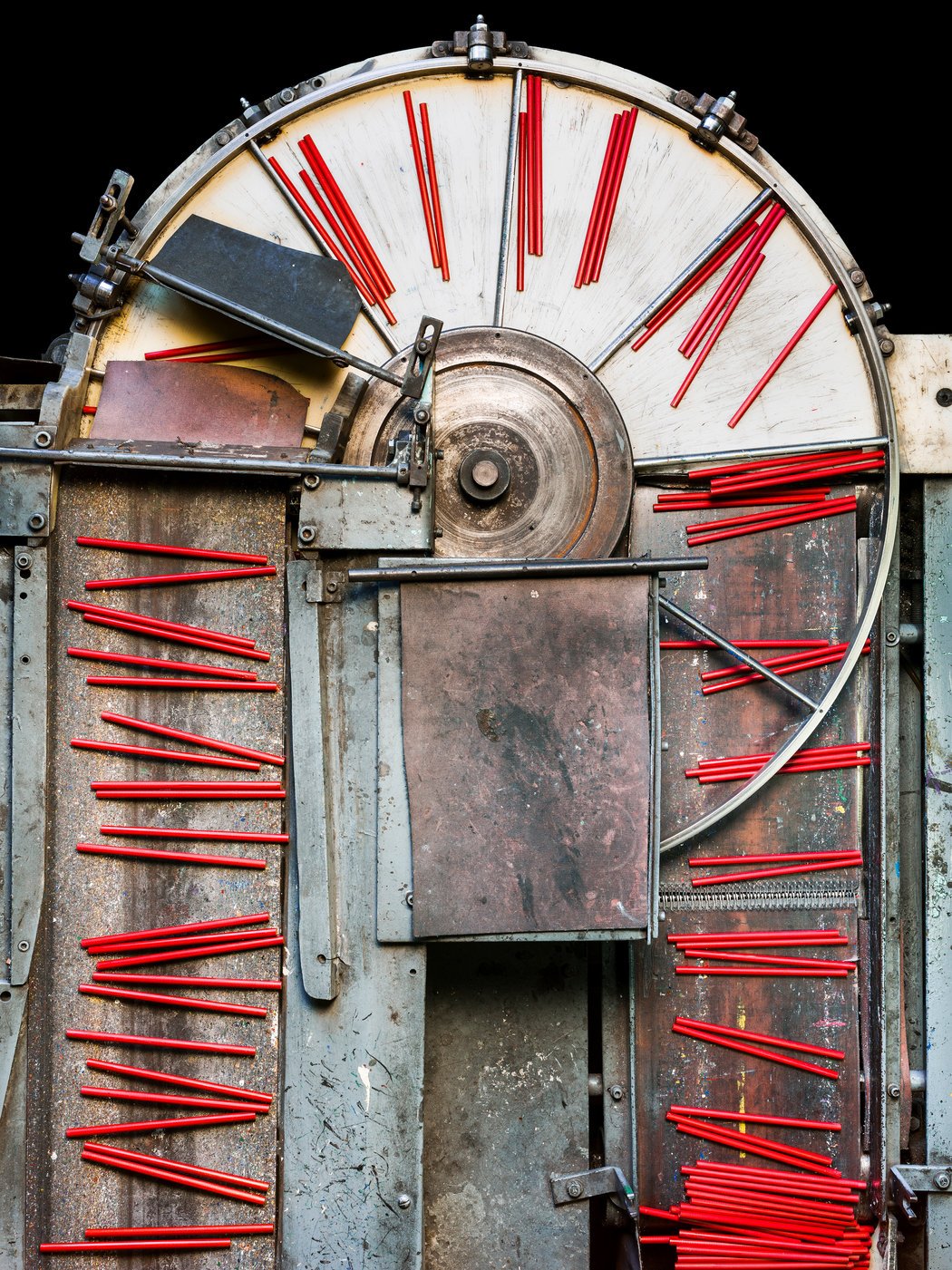

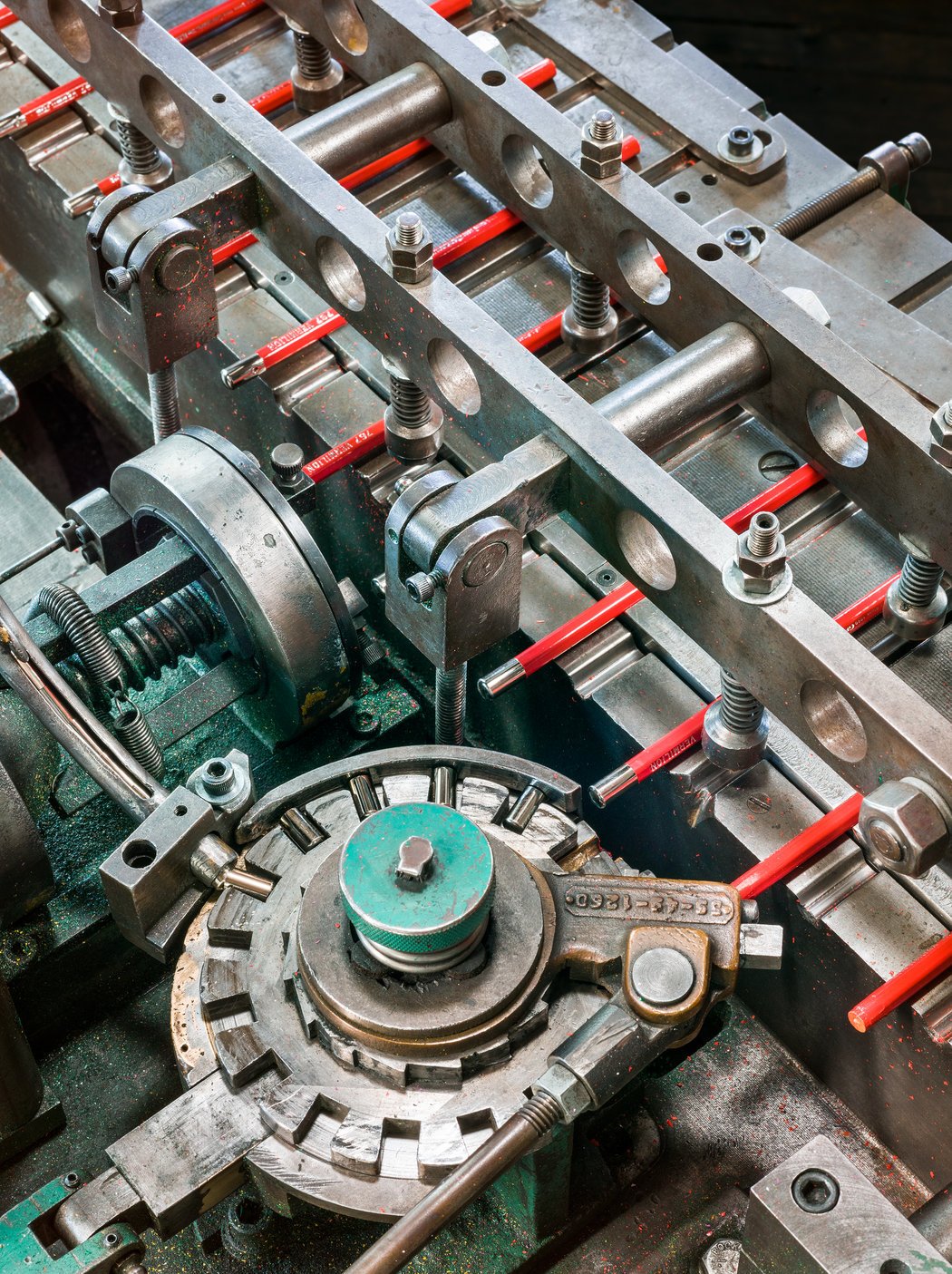

Other parts of the factory are eruptions of color. Red pencils wait, in orderly grids, to be dipped into bright blue paint. A worker named Maria matches the color of her shirt and nail polish to the shade of the pastel cores being manufactured each week. One of the company’s signature products, white pastels, have to be made in a dedicated machine, separated from every other color. At the tipping machine, a whirlpool of pink erasers twists supervised patiently by a woman wearing a bindi.

Payne conveys the incidental beauty of functional machines: strange architectures of chains, conveyor belts, glue pots, metal discs and gears thick with generations of grease. He captures the strangeness of seeing a tool as simple as a pencil disassembled into its even simpler component parts. He shows us the aesthetic magic of scale. Heaps of pencil cores wait piled against a concrete wall, like an arsenal of gray spaghetti. Hundreds of pencils sit stacked in honeycomb towers. Wood shavings fly as fresh pencils are dragged across the sharpening machine, a wheel of fast-spinning sandpaper.

In an era of infinite screens, the humble pencil feels revolutionarily direct: It does exactly what it does, when it does it, right in front of you. Pencils eschew digital jujitsu. They are pure analog, absolute presence. They help to rescue us from oblivion. Think of how many of our finest motions disappear, untracked — how many eyes blink and toe twitches and secret glances vanish into nothing. And yet when you hold a pencil, your quietest little hand-dances are mapped exactly, from the loops and slashes to the final dot at the very end of a sentence.

Photographs like these do something similar. They preserve the secret origins of objects we tend to take for granted. They show us the pride and connection of the humans who make those objects, as well as a mode of manufacturing that is itself disappearing in favor of automation. Like a pencil, these photos trace motions that may someday be gone.

Credits: nytimes.com