On November 13th, 1974, six members of the DeFeo family—father Ronald, mother Louise, two daughters and two sons—were shot to death in their beds there in their home at 112 Ocean Avenue. A third son, 23-year-old Ronald “Butch” DeFeo, Jr., initially told police he’d innocently discovered the bodies in the locked house around 6 p.m. later that day. As Butch DeFeo told the story that day, when he saw the bodies, he fled the house to a bar down the street, arriving there in a state of “hysteria,” as one man lingering at the bar told reporters. He took the men back to the house and the police were called, who doubted Butch’s claims to innocence almost immediately: Within two days of finding the bodies, he would be on the hook for six second-degree murder charges; the police had come to believe that he’d committed the crimes because he wanted insurance money, a sum of about $200,000. ($960,000 today, adjusting for inflation.)

DeFeo’s attorney was a bald-pated, laconic man named William Weber. From the time of his arraignment, Weber insisted that DeFeo was insane. They blamed the dead Ronald DeFeo, Sr. for his son’s dysfunction, arguing that he had been an abusive, bullying man. By the time the case came to trial, in October 1975—just months before the Lutzes would buy the Ocean Avenue house and move in—DeFeo’s lawyers had hired a psychiatrist who said that their client had been in a state of “paranoid psychosis” as he moved through the house and shot each of his relatives, one by one.

A psychiatrist hired by the prosecution agreed that DeFeo was mentally ill, but insisted that he still knew that what he had done was wrong, and therefore didn’t fit the legal definition of insane. The jury sided with the prosecution. DeFeo received six concurrent life sentences for the deaths of his siblings. When a Newsday reporter at the trial asked Weber if he thought the verdict against his client was fair, he did not reaffirm his client’s innocence or make the usual strident sort of statement one expects from a criminal defense attorney. Instead, he shook his head, and said, “I’m glad I wasn’t a member of that jury.”

But Weber clearly still wanted to try to argue the case. He had said to reporters during the trial that he was charging DeFeo only a “modest fee,” and that “I’m getting more out of this from the publicity.” The tale of a haunting gave Weber a chance to put the case back into the spotlight. It was, in fact, in Weber’s office that the Lutz’s February 1976 press conference took place, although he did not present himself as their attorney. Weber told reporters that day that now, having heard the Lutz family’s full story, the story they were not entirely sharing that day with reporters, he thought he could reopen the DeFeo case.

The implication was clear: the tale of paranormal phenomena in the house suggested that DeFeo had, in fact, been out of his mind—he’d been driven out of it by this supernatural current in the place. Of course, Weber said, he could not tell them more just then. He still had to discuss it with his incarcerated client. He was looking into filing a motion, he said, though he never said what kind and none appears to have ever been filed. As of right now, Ronald DeFeo is still an inmate in a correctional facility in Fallsburg, New York.

For fourteen months after the Lutzes fled the house in Amityville, it stood empty. Then, a family called Cromarty had moved into the house in the spring of 1977. “We moved in on April 1,” Jim Cromarty would later tell a reporter, “We were out here like a week and then came this Good Housekeeping article. We started to get a lot of visitors.” The Good Housekeeping article, by a man named Paul Hoffman who’d repeatedly written about the case for the New York Daily News, was published in the April 1977 issue, under the title “Our Dream House Was Haunted.” The article would swiftly become the subject of a lawsuit by the Lutzes, who claimed the article invaded their privacy. (This lawsuit, in which the Lutzes sued Hoffman, Good Housekeeping, the New York Daily News and several other parties for invasion of privacy, ultimately wasn’t successful. The publications were thrown out of the case by judges, and claims against Hoffman and the remaining defendants were eventually settled for undisclosed terms in 1979.)

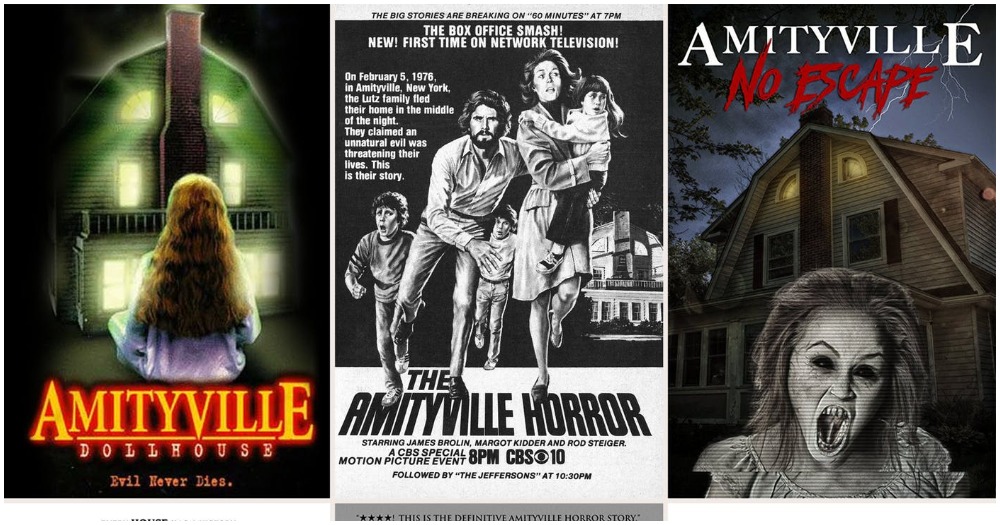

Then, five months later, Jay Anson published the book he’d written with the Lutzs’ input, The Amityville Horror. “A Devil of a True Story,” the Los Angeles Times reviewer called it. The book swiftly hit the bestseller lists and stayed there for 42 weeks. By 1981, the book had gone through 37 printings and sold over 6.5 million copies. The film rights sold to Hollywood, with Anson attached to write the screenplay.

But as the phenomenon grew, there were two key doubting voices. Throughout their ownership of the house, which lasted a decade, Jim and Barbara Cromarty repeatedly told the press they’d never seen anything unusual in the house. (That should have been good news. They had bought the place cheap because of all the bad publicity—they’d bought the house for $55,000 where the Lutzes had bought it for $80,000.)

Instead of spirits, the Cromarty complained, they were haunted by what could only be called paranormal tourists, who knocked on the door at all hours of the day and night. These people sometimes called themselves witches. Sometimes they cursed out the Cromartys and told them they would die. Sometimes they were drunk. And sometimes, as the family told Newsday in 1978, they were just odd: “I think one of the funniest things was when we woke up at three o’clock and heard this guy with a bugle playing ‘Taps’ on the front lawn. I opened the window and applauded and said, ‘Kid, you’ve got a real good sense of humor,’” said Jim Cromarty.