There were haunted houses before Amityville, of course, but no one place has made as deep an impression on American pop culture in the past half-century or so as the notorious Long Island home, the site of a terrible murder and then the basis of scores of books and movies.

HISTORY DOES NOT RECORD what a bunch of Long Island newspaper reporters thought they would hear on February 13, 1976, as they were hustled into a modest, book-lined attorney’s office in the village of Patchogue, New York. In that room, that morning, the press would be introduced for the first time—but certainly not the last—to George and Kathleen Lutz, two relative newlyweds of indeterminate employment who had, very suddenly, left their dream house in Amityville the month before. Rumors had been floating through this sleepy area on the south shore of Long Island that the Lutzes had left because the house was haunted.

George and Kathy Lutz, in their mid-thirties, looked like a normal couple, at least normal for the ‘70s: he had lots of pin-straight light-brown hair and a full beard, she had a blonde feathered haircut that framed a round, sweet face. In the press conference, George did more of the talking. He took the tone of someone who had been forced, reluctantly and after long consideration, to come forward with his story. He said he didn’t want to get into details. But yes, he said, a “very strong force” had driven his family from the house. He wanted, too, to correct some facts. No, his family had not seen “human shapes” and “flying objects” in their home.

No, they had not heard “wailing sounds” and seen “moving couches.” But yes, they had left the house after only owning it for a month, with just three changes of clothes apiece, “because of our concern for our own personal safety as a family.” And that was about all he was willing to share for the present time. The reporters tried to press Lutz for more details, but he would not be specific, as the Newsday writer reported with evident frustration. “[Lutz] did say he would not spend another night in the house if asked to do so by researchers, but he also said he is not planning to sell the house right now,” the reporter wrote.

Within a day of the press conference, the lawn of this house, a Dutch Colonial perched on a waterway at 112 Ocean Avenue, was full of people who had decided to come investigate matters themselves. They came mostly from neighboring towns in Long Island. They parked along the street. Some were accompanied by their children. “I’m interested in unexplained… phenomena,” said a father who’d brought his 12-year-old son. “I was here the other night with my other son, and we watched the electric meter for a while—and I swear it slowed down… of course, it could have been the refrigerator.”

One would like to believe that journalists have enough common sense not to believe in ghosts. But in the 1970s, American culture was awash in superstition. It was a time rather like our own, filled with economic and political instability. The Lutz family’s press conference took place 18 months after Watergate had forced Richard Nixon to resign the presidency and the onslaught of upsetting news had led everyone to question conventional facts and truth. It was unclear whether the stable laws of the universe still held.

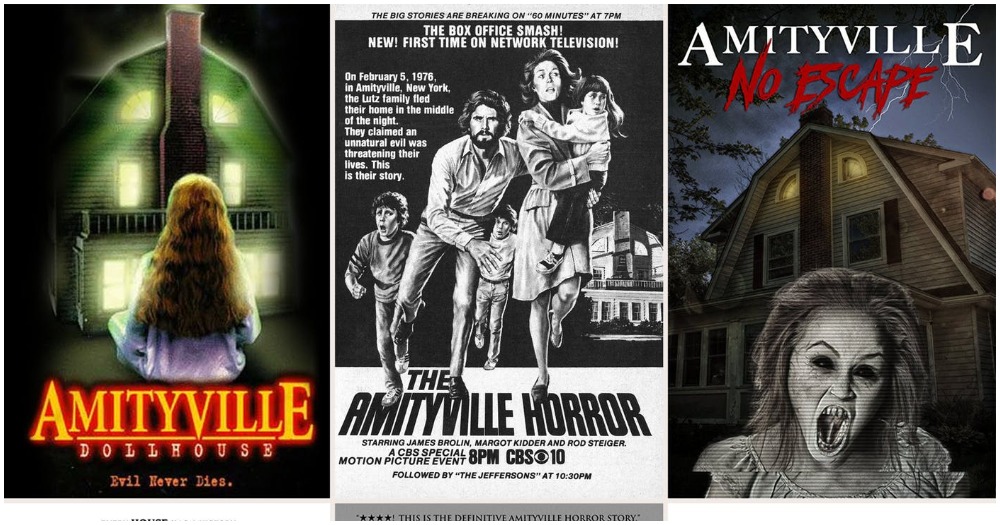

Anger and fear were everywhere, and often enough, they bloomed into outright delusions. Couple that with the remnants of the New Age philosophies of the 1960s, shake in a little bit of good old American folklore, and you got something like what the Lutz family’s story would eventually be: The Amityville Horror, a story that would inspire several books and more than half a dozen films, spanning from the 1979 original blockbuster starring James Brolin and Margot Kidder, to the rather poorly-reviewed, middling effort released just this past October 12, called Amityville: The Awakening, starring Jennifer Jason Leigh and Bella Thorne. Though a lucrative and ubiquitous emblem of American mythology, it’s telling how dull the story actually is, when summarized: Young American family moves into house where there was once a mass murder. Disturbing phenomena follow, including (as reported in the first book on the case, written by a man named Jay Anson with the paid cooperation of the Lutzes, and later in the screenplay Anson wrote for the 1979 film version) green slime leaking from the house’s keyholes, a spirit yelling “Get out!” to a visiting priest, a child beginning to speak to an imaginary friend named Jodie. The father sees, in a window, a pig with red, glowing eyes. Cold spots appear mysteriously in the house. A roomful of flies torments the family. Eventually, the family has enough, and flees. Research eventually tells them that their house was not only the scene of a murder but the alleged site of an ancient “enclosure for the sick, mad and dying” operated by the Shinnecock Indian Nation.

Many of these elements were already part and parcel of the American horror story, especially that last one – the rather racist tracing to the “Indian burial ground,” which had long been a kind of catch-all explanation for paranormal phenomena in American storytelling. The notion had, for example, also surfaced repeatedly in the work of Stephen King, in The Shining and Pet Sematary. Pike Place Market in Seattle is thought to have been built on a Sqaumish Indian ground, and people also claim it is haunted. What was unusual about The Amityville Horror, though, was that in a way, the story-about-the-story was more interesting than the alleged haunting itself. It hovered on a strange, tricky edge of fact and fiction. Some players, from the start, were upfront about admitting it was a hoax. Others insisted, to their graves, that the story was true, that the Lutz family had been haunted by something. It’s just that the something may not have been paranormal at all.