The kidnapping of Patty Hearst can seem as distant in time as a yellowed newspaper clipping — and as current as today’s bit-borne headline.

Fundamentally, though, the story is timeless, because at its core it’s a mystery about why human beings do what they do. And the key elements that play out in the saga — terrorism, the role of the media, wealth and celebrity — are as relevant today as they were more than 40 years ago.

The rough outlines of the story will be familiar to news consumers of a certain age: On February 4, 1974, Patricia Campbell Hearst, heiress to the greatest newspaper fortune in the land, was kidnapped from her home in Berkeley, California, by a little-known revolutionary cell called the Symbionese Liberation Army.

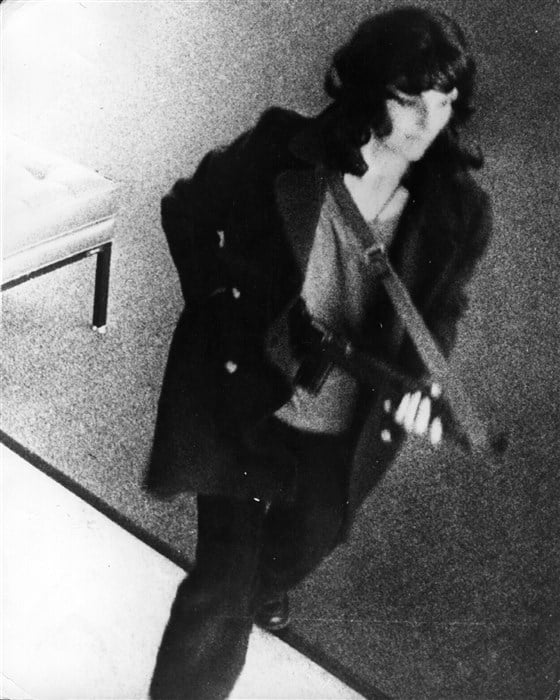

Within weeks, she stunned the world by announcing that she had joined forces with her captors and was seen wielding a machine gun as the group robbed a bank in San Francisco.

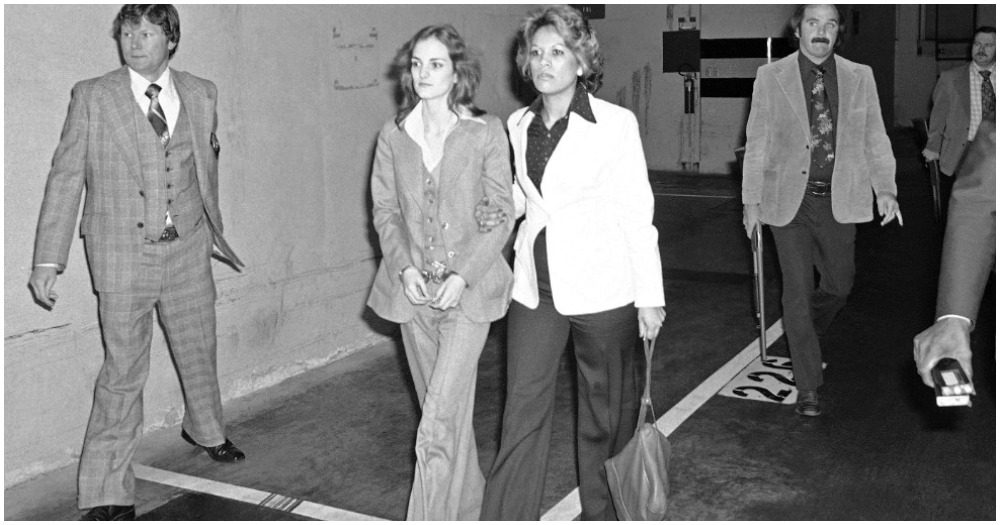

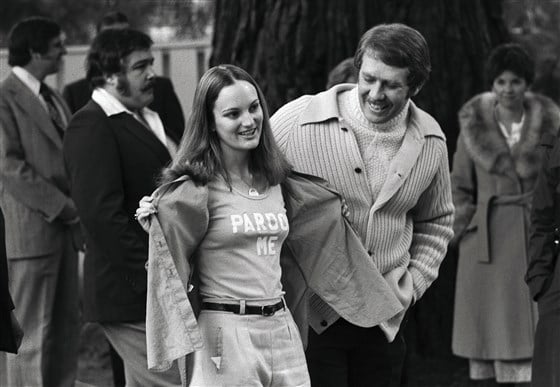

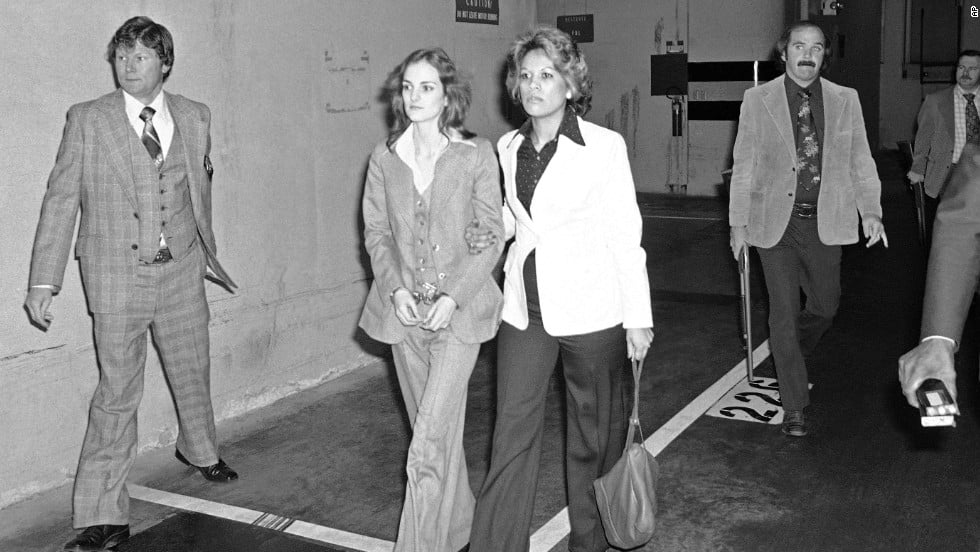

Following a bumbling manhunt by the FBI, six members of the SLA were cornered and then killed in a shootout in Los Angeles. Hearst was elsewhere at the time and spent the next year and a half on the run from the authorities. Once she was captured, Hearst was placed on trial, defended by the legendary F. Lee Bailey, and ultimately convicted of the armed bank robbery.

The case captivated the entire country as it stirred the national consciousness about issues such as brainwashing, free will and the collective insanity that gripped the United States in the 1970s.

But whether you can recall those moments or not, the same thing is true: When it comes to the Patty Hearst kidnapping, you don’t know the half of it.

Consider, for example, the subject of terrorism. We live today in the shadow of ISIS and al Qaeda, and the threat of random bombings haunts both the public and the government that is supposed to protect us.

But the threat of a bombing was far greater in the 1970s — and these weren’t just threats, they were a reality. There were more than 1,000 politically inspired bombings every year in the United States during the early part of the decade, and politically inspired violence became a fact of everyday life. So the kidnapping of Patty Hearst was aberrational, but not that far afield from what was already happening — and that alone was a sign of how close our country was in those days to a collective nervous breakdown.

There’s also the place of the news media in our society at the time. In the ’70s, a family that owned newspapers could still be considered one of the most famous and wealthy in the nation. But the news business as a whole was a much smaller enterprise in those days. In that pre-cable and pre-internet era, national news consisted little more than three evening news shows and the “Today” show in the morning. (“Good Morning America” did not begin until 1975.)

News technology was in its infancy, too, but the change was coming — and, of course, this kidnapping helped bring it about. A pioneering local news operation in Los Angeles sent a newfangled contraption called a minicam to the SLA shootout in Los Angeles, and the conflagration wound up being broadcast live around the country. This became the new standard for news, and everyday coverage — to say nothing of Bronco chases — was never the same.

Still, the heart of the Hearst story is the mystery of the woman herself. At her trial, in her memoir and in many years of interviews (Hearst declined to talk to CNN for our documentary), she has maintained that she was coerced and abused by her captors, and she has insisted that she only participated in their crimes because she feared being killed by them if she refused.

Her prosecutors have always regarded her very differently, and their words — and even their names — also have a contemporary resonance. When Hearst applied for a presidential pardon in 2000, the US attorney in San Francisco objected in outraged terms. “I strongly oppose the pardon application filed by Patricia Hearst,” the US attorney wrote, “The attitude of Hearst has always been that she is a person above the law and that, based on her wealth and social position, she is not accountable for her conduct, despite the jury’s verdict.”

Credits: cnn.com