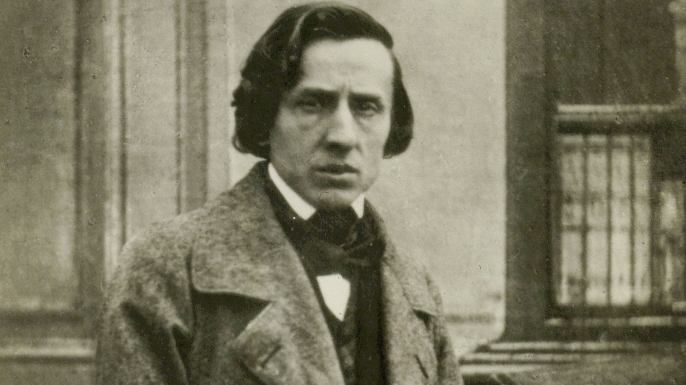

It’s usually very hard to figure out the diseases historical figures died from. Case in point: it took over 150 years for researchers to figure out that composer Frédéric Chopin died of pericarditis—a rare complication of tuberculosis that causes swelling around the heart—and only then because they were able to study his actual heart, which had been pickled.

Yes, you read that correctly. Chopin’s heart has been carefully preserved since his death in 1849. Before he died, he asked that his heart be cut out and buried in Poland, his homeland. His last known words, according to Nature, were: “Swear to make them cut me open so that I won’t be buried alive.”

Chopin had taphephobia, the fear of being buried while still alive. Back in his day, there were no machines to tell observers when an ailing person had “flatlined,” so declaring someone dead was an imperfect process, based on guesswork. Chopin was far from the only famous figure who suffered from this macabre phobia; taphephobia was actually fairly common at the time.

George Washington was so afraid of being buried alive that he wanted his seemingly deceased body to be laid out for three days, just to make sure he was really dead, writes Sarah Murray in Making an Exit. Writer Hans Christian Anderson and Alfred Nobel, who established the Nobel Prizes, also shared this fear and wanted their veins to be opened after they appeared to die to make sure they were really gone.

According to Kenneth V. Iserson, professor emeritus of emergency medicine at the University of Arizona and author of Death to Dust, that fear was based on a historical reality with deep roots.

“We know that there was a fear of being buried alive as early as Biblical times,” he says. Back when Jesus supposedly raised Lazarus from the dead, it was common to wrap dead bodies and bury them in caves. Then a few days later, someone would go check to make sure they weren’t still alive. The reason people would do this is that sometimes, they were.

In cases where people were mistakenly buried alive, “we’re not exactly sure of what diseases they had,” Iserson says. In the 19th century, it’s possible that typhoid, which makes the pulse very slow, led to some premature burials, but in general, it’s hard to determine how famous figures died from historical records alone, since the way people of the past understood the disease is very different from how we do today.

For most of history, tools for measuring the body’s functions were imprecise, and the only surefire way to tell if a person had died was to leave the body out and see if it decayed.

“Think about it,” Iserson says. “How do we really, really know a person is dead? Nowadays, it’s not just by looking at them”—it’s with modern technologies like electrocardiograms.

That’s why there are many verifiable cases of people being buried alive, even into the 20th century. One example is Essie Dunbar. In 1915, Dunbar had an epileptic attack in South Carolina and was pronounced dead. At the funeral, her sister arrived after the ministers had already lowered the coffin, and they agreed it bring it up again so she could see her one last time.

“But when the screws were removed and the coffin lid opened, Essie sat up in her coffin and smiled at her sister,” writes medical professor Jan Bondeson in Buried Alive. “The mourners, including Essie’s sister, believed that she was a ghost, and fled yelling.”

In Essie’s case, she’d probably had a seizure that made her lose consciousness, leading people to believe she was dead. After this harrowing experience, she lived for several more decades until her real death, in 1955.

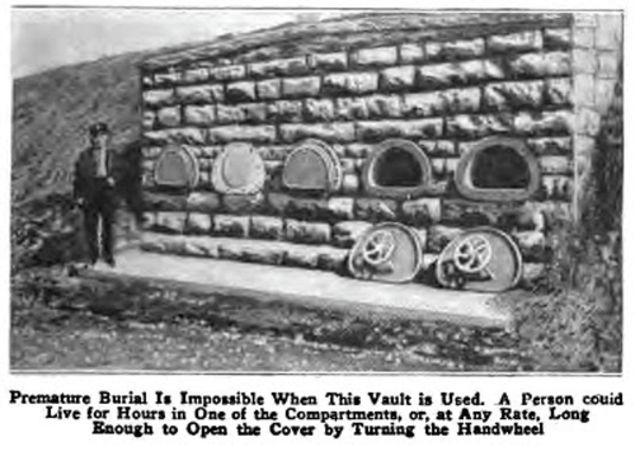

Fear of being buried alive reached its commercial peak during the Victorian era when inventors began to capitalize on people’s worries with “safety coffins.” Some were basically aboveground tombs with a hatch that the buried person could unscrew if they woke up. Others were attached to an aboveground bell that a person could ring from her coffin if she woke up, or connected to tubes that went aboveground so gravediggers could check on the bodies.

Buying these elaborate coffins may have been a way for people to assuage their fears of being buried alive, but Iserson notes that there are no verified cases in which they saved someone’s life. In any case, the fear of being buried alive started to fade during the 20th century as new funeral practices took over. After creating a body or embalming it with formaldehyde, one can be absolutely sure that that person is dead.

Yet people do occasionally still wake up in morgues. In November 2014, mortuary staff saw a 91-year-old Polish woman moving in her body bag and discovered she was alive. Two similar instances happened earlier that year: one in Kenya and one in Mississippi.

So while it was pretty dramatic for Chopin to instruct people to cut out his heart to make sure he was dead, considering the time period—and the recent incidences at morgues—it might be one that even modern readers can understand.

Credits: history.com

Share this story on Facebook with your friends.