While viewers had met him as costumed hero Kato, the martial arts-wielding sidekick to Van Williams’ title character on the 1967 TV series The Green Hornet, movie audiences began to recognize the star potential of Bruce Lee in several films released during the Kung Fu movie craze of the early 1970s. And while Bruce, who would have been 80 this year, could see his star rising, tragically he never saw how big a phenomenon he would become. He died at age 32 of a cerebral edema on July 20, 1973 at age 32, less than a month before the release of his seminal contribution to the genre, Enter the Dragon. His legend has only grown since then.

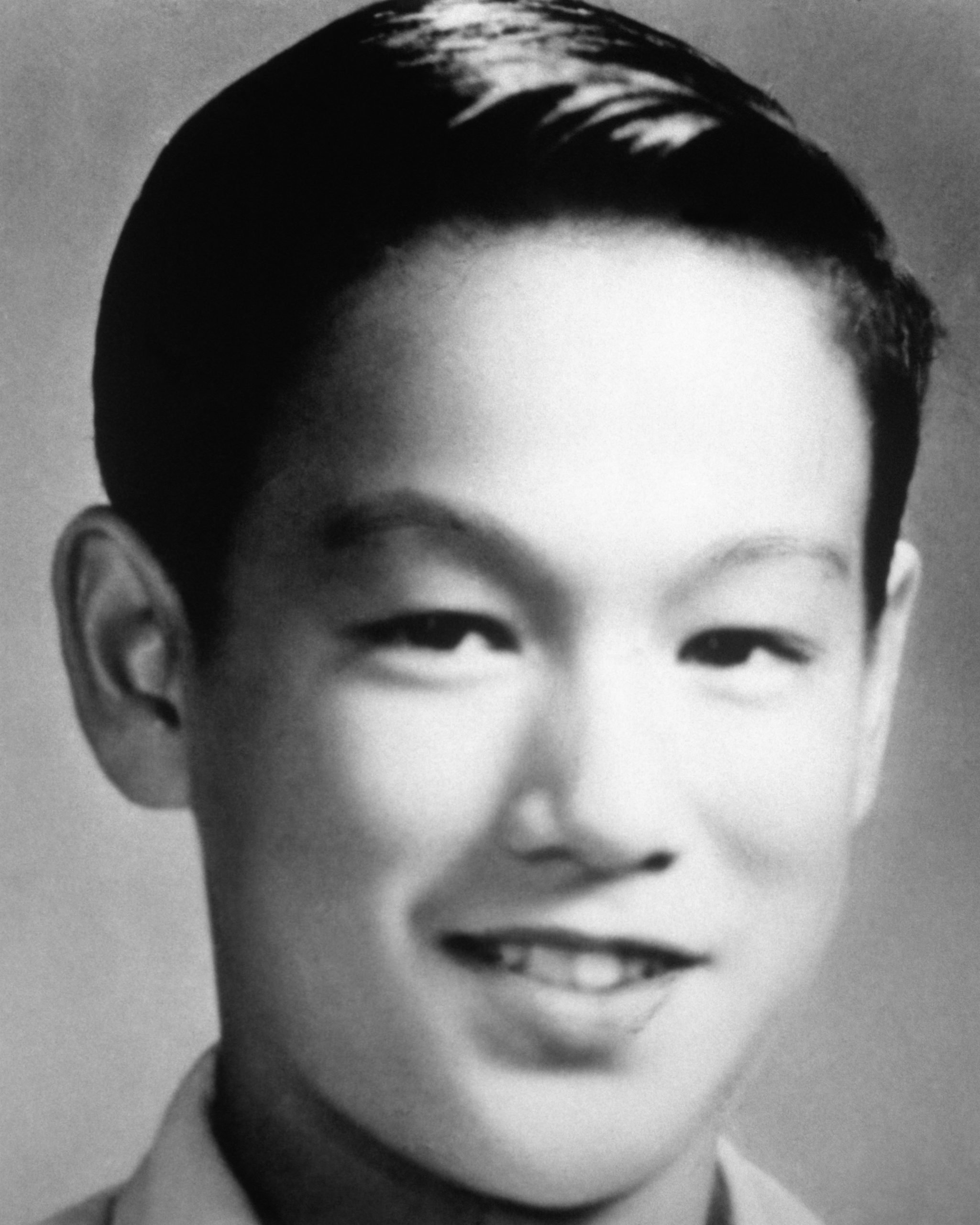

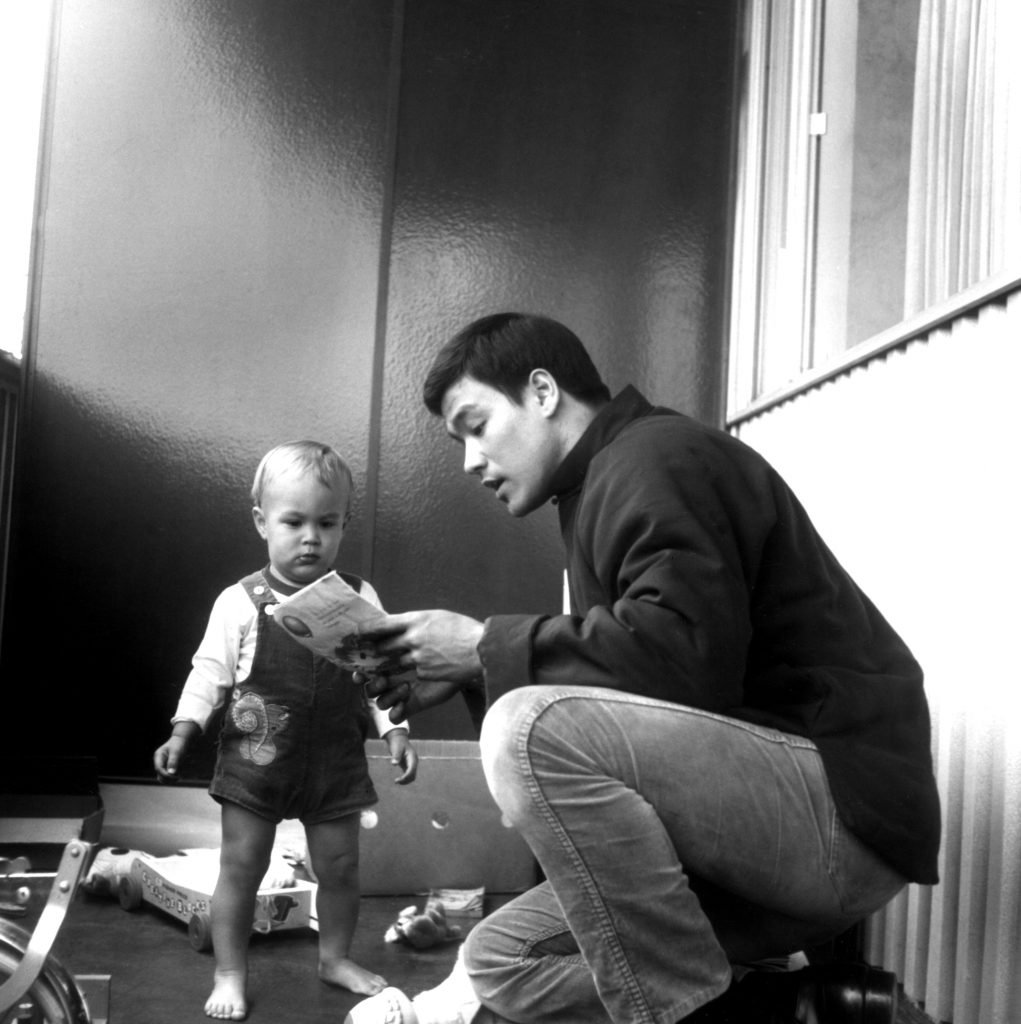

Born November 27, 1940 in San Francisco, California, the Hong Kong-American actor and his family would return to Hong Kong three months later. As a child actor, he appeared in 20 films, but in his private life he was running into problems at school and with gangs and, to keep him safe, sent him to San Francisco to live with older sister Agnes Lee. There he would continue his education and focus on his interest in both acting and the martial arts, developing the Jeet Kune Do martial arts philosophy.

Over the next decade he would achieve acclaim with his martial arts skills, instructing many students — actor Steve McQueen, among them. He began making films in Hong Kong and grew in popularity there, which set him up perfectly when those films found a huge market in America. This would, as noted, lead him down the road of posthumous super stardom.

RELATED: Bruce Lee’s Only Real Fight Ever Recorded Surfaces; Very Rare

Bruce Lee’s life and career is the subject of Matthew Polly’s definitive biography, Bruce Lee: A Life. What follows is an exclusive interview with the author, who reflects on the legacy of “The Little Dragon.”

How did your view of Bruce Lee change from when you began this book to when you had completed it?

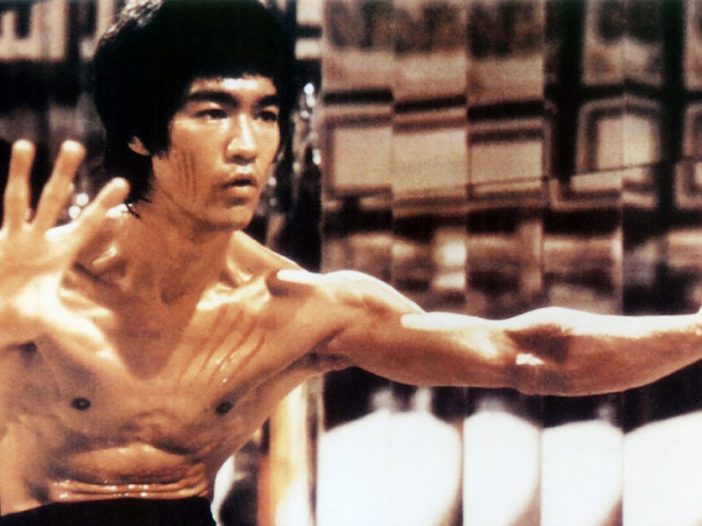

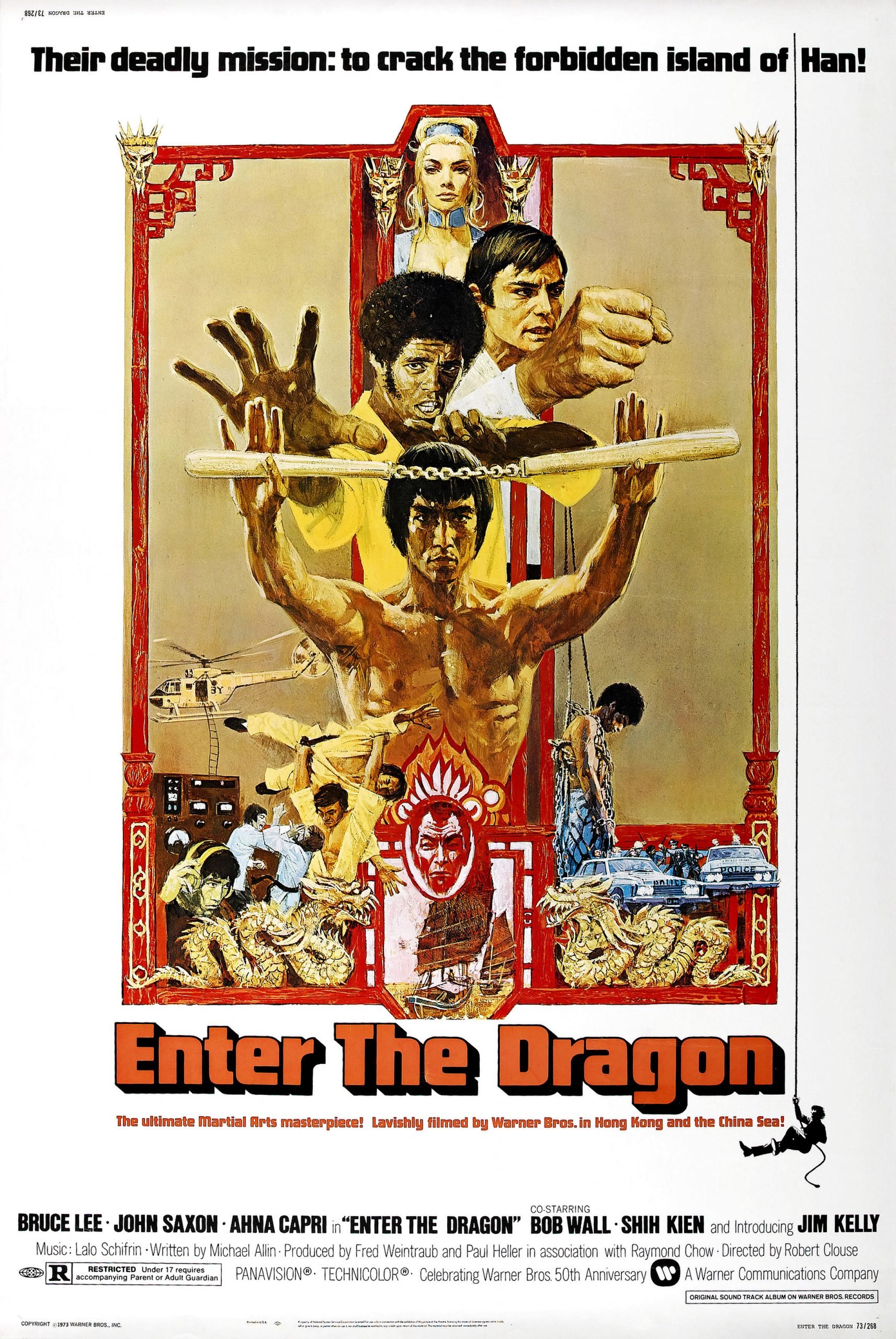

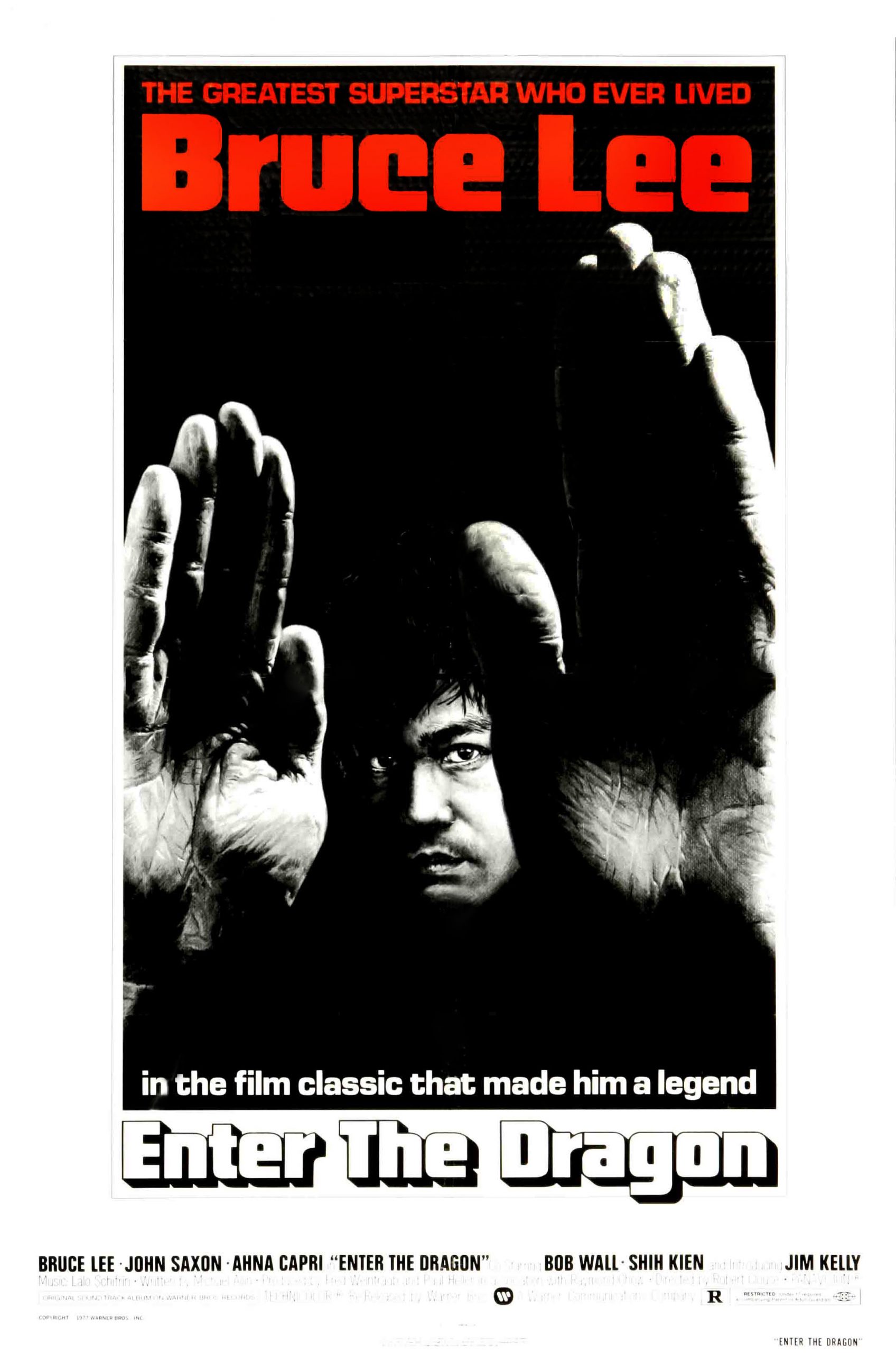

MATTHEW POLLY: I think there were two big revelations for me. One was overarching, and that was that Bruce Lee as I had encountered him as a kid, and I think every one of us encountered him, was the guy in Enter the Dragon. He was the character. The reason why is that he’s the only iconic figure of the 20th century whose fame was almost entirely posthumous. He died before the movie that made him famous actually made him famous, and there was no encounter with him beforehand as a celebrity persona. So even James Dean or Marilyn Monroe — they were all famous before they died early. With Bruce lee, aside from The Green Hornet and the few martial arts fans who were into him, no one knew who he was, and so Enter the Dragon was our only text to understand him.

Then the martial arts magazines ran with it, and they turned him into the patron saint of Kung Fu, which is true as far as it goes, but the first huge revelation was when I was sitting in the Hong Kong film museum watching the 20 films he made as a child actor in Cantonese and Mandarin, and I was like, “Not one of these has any fight scenes.”

Which, one would imagine, presented quite a contrast to what we were used to when hearing his name.

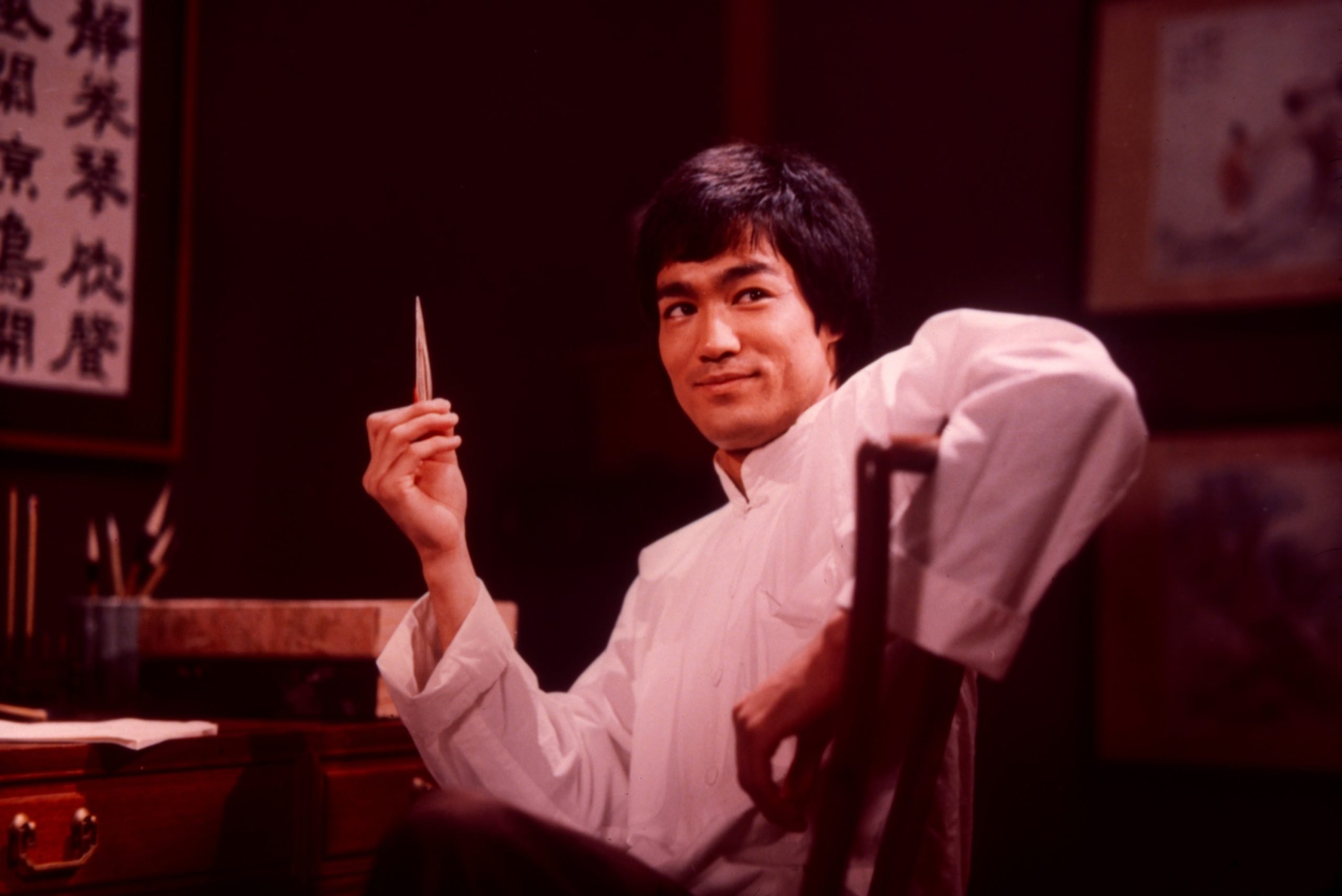

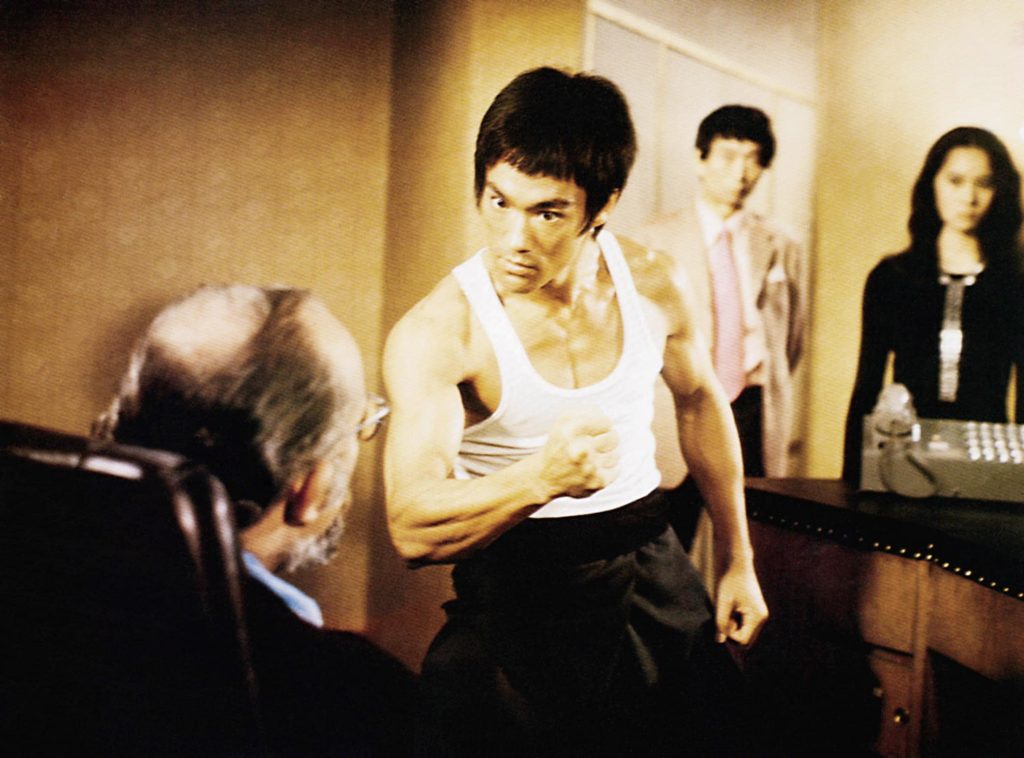

MATTHEW POLLY: Exactly. Twenty films is a lot. He had a full career in which he played spunky orphans in melodramas and weepies. There’s a sense that here’s an actor who fell in love with the martial arts, and then merged his two obsessions by becoming a martial arts actor. That was later in like phenomenon, and what he was first and foremost was an actor growing up in the entertainment industry as a child actor. That gave me a sort of way to understand things that people had written out of his history, because it didn’t fit with the patron saint of Kung Fu image. You know, that he had a Mercedes-Benz and he bought a full mink coat and smoked a little dope and had a few extramarital affairs. And his behavior as an adult was like Steve McQueen, who was his role model. He was a celebrity. He wasn’t an aesthetic guru Zen martial arts monk. That was the character he played in Enter the Dragon, but that’s not who he was as a person. As a person he was an actor first chronologically, and then he became a Kung Fu expert.

There was a world of difference between his previous films and ‘Enter the Dragon,’ which in a sense crystallized the persona we became used to.

MATTHEW POLLY: That’s how his image was formed and it’s a distinct one, because if you think of him as a celebrity actor who’s into Kung Fu, then he becomes like many of the actors at the time. But if you only think of him as a Kung Fu master who accidentally made films, then he becomes distinct, almost a demi-god the way the fans think of him. He’s invincible. They sit around arguing could he beat Iron Man in a fight, you know? So he becomes a character, and that’s what’s fascinating to me. They start making Bruce-sploitation movies where he fights Dracula and James Bond and he becomes a fictional character. That only happens because I think there was no long history of seeing him on the Johnny Carson show or seeing him in the gossip mags, and all the things that accumulate around a celebrity so that we hold them distinct from the characters they play on screen.

What’s fascinating is that he tried to present himself in a certain philosophical way, but he was absolutely driven by a lot of the same foibles as everyone else.

MATTHEW POLLY: And I thought that was amazing. I don’t want to denigrate his dedication to his beliefs, because he was very serious about it. I would talk to people who were like, “Yeah. He just wouldn’t shut up.” That’s not somebody who’s faking it, you know? Somebody who’s constantly talking about it all the time is somebody who’s a true believer. But I think psychologically speaking, he was trying to balance himself out and that, at root, the Little Dragon had a hot temper and burned the candle at both ends. He had this great charisma, he had star power, and all the imagery when people talk about Bruce is very fire-oriented. Yet what he talked about was, “Be like water, my friend.” I believe that was him in some sense knowing what his weakness was, and trying, through philosophy, to balance himself out. So when you study his life, you see all those kind of firey things — the short temper, the getting into fights, the arguing with people above him. Then you hear his philosophy, which is be like water, adapt, bend with the wind. We preach what we need to practice, right? If you listen to a man preach about not having extramarital affairs, you know what you’re going to find out.

Many people don’t want their view of celebrities to clash with the fact they’re only human.

MATTHEW POLLY: And that was the goal of the book, to show how Bruce was human, because I think his accomplishments are more remarkable if you treat him as a human being and see what he had to overcome in order to became the first Asian American to star in a Hollywood movie. As opposed to treating him as a super heroic character who just rolled out of bed one day and had this tremendous success.

Given excerpts pre-publication, there was a sense that it would be pretty salacious, but that wasn’t the case. Also, how does this book contrast with the official image the Bruce Lee estate has spent decades cultivating?

MATTHEW POLLY: When I read the Daily Mail excerpt, I actually was blushing. I was, like, “Who wrote that book? That’s trashy.” I wanted to tell his story, soup to nuts, warts and all, but his flaws are just a small part of his story. I wanted to put everything in context, so of a 600 page book, maybe six pages deal with extramarital flings. But, of course, the Daily Mail picked out each one of them and shoved them to the top.

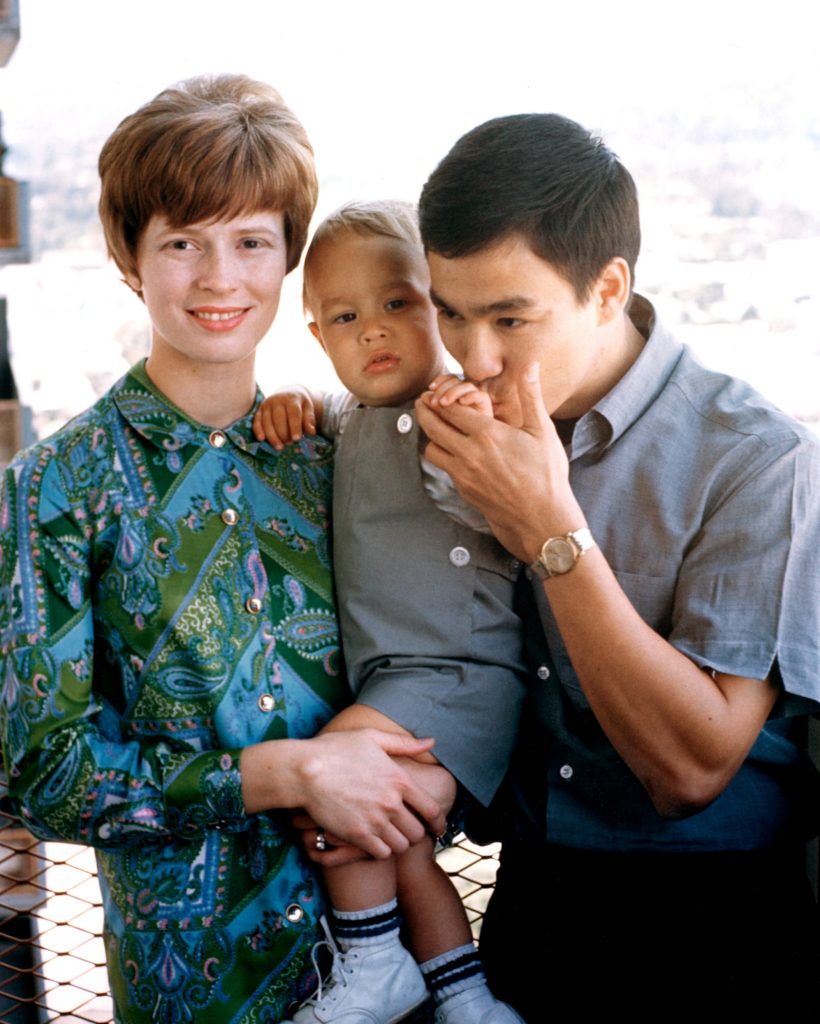

Let me bracket that sort of carefully by saying I spoke with Linda and I spoke with Shannon [respectively Bruce’s widow and daughter]. I like them both and admire the way they worked so hard to keep Bruce’s image alive and talk about his philosophy and the values that he espoused. The image they presented was one of “Saint Bruce.” I wondered if it was monetary or if it was true belief, but when I talked to Linda, and I was interviewing her, my feeling was, “My god, she really does believe that he is perfect.” She wasn’t fully convinced that stories of his cheating were true. I’d written a piece where I’d said Betty Ting Pei was his girlfriend, and she hadn’t agreed to the interview until she read that piece, and she basically came in to correct me. She said, “Well we don’t know this is true,” and I was like, “So you don’t believe it?” “Well, he was such a good father and he was such a good husband. I don’t think he would do anything to hurt his family.” At that moment I was, like, “Wow. Okay.”

I think to this day he was the true love of her life, her first true love, and she just has a remarkable love for him. I’ve been at events where she’s spoken to students of his and rattles off the things that Bruce said. I just was, like, “She’s a bit of a high priestess of the church of Bruce.” I think it’s quite sincere, which is my point. Secondarily, everything the Bruce Lee estate does is as policy. They don’t get involved with anything that touches on his death, and so when you see anything that’s been authorized by the Bruce Lee estate, what you’ll see is it’s his whole life and then there’s an ambulance driving by. Then we get into the afterwards. So they made a policy of never touching on his death, which involved a lot of the scandal and as a result it creates a distorted image of who he was.

The impression from the book is that she’s still involved with cleaning up the mess, so to speak.

MATTHEW POLLY: Part of the reason that the end of Bruce’s life is something they don’t care to talk about is that there was a coroner’s inquest, and she had to testify. There was a lot of things about what happened on that last day that are questionable. The very first thing that happened after Bruce died is Golden Harvest [studio] put out a statement saying he died at home with his wife, walking in the garden. So they covered up from the very beginning in order to try to deny an affair. This story got blown up three days later by the press, and then they came out with another story which was that Raymond Chow and Bruce went over together to Betty’s apartment for a business meeting to offer her a role in Game of Death.

Raymond Chow doesn’t go to business meetings at the apartments of B list actors at this point. No movie executive does that. He had meetings in fancy restaurants or at his office. So the second story, which held up for a really long time, which no one believed, but no one could puncture, was also made up. It was a slightly altered version in order to cover up the affair. Then, finally, when I interviewed Betty in 2013, that was the first time she told a Western reporter, “Look I was his girlfriend.” He came over by himself. So the cover up has lasted a long time and to a certain extent everybody was involved with it, including Betty, Raymond and Linda.

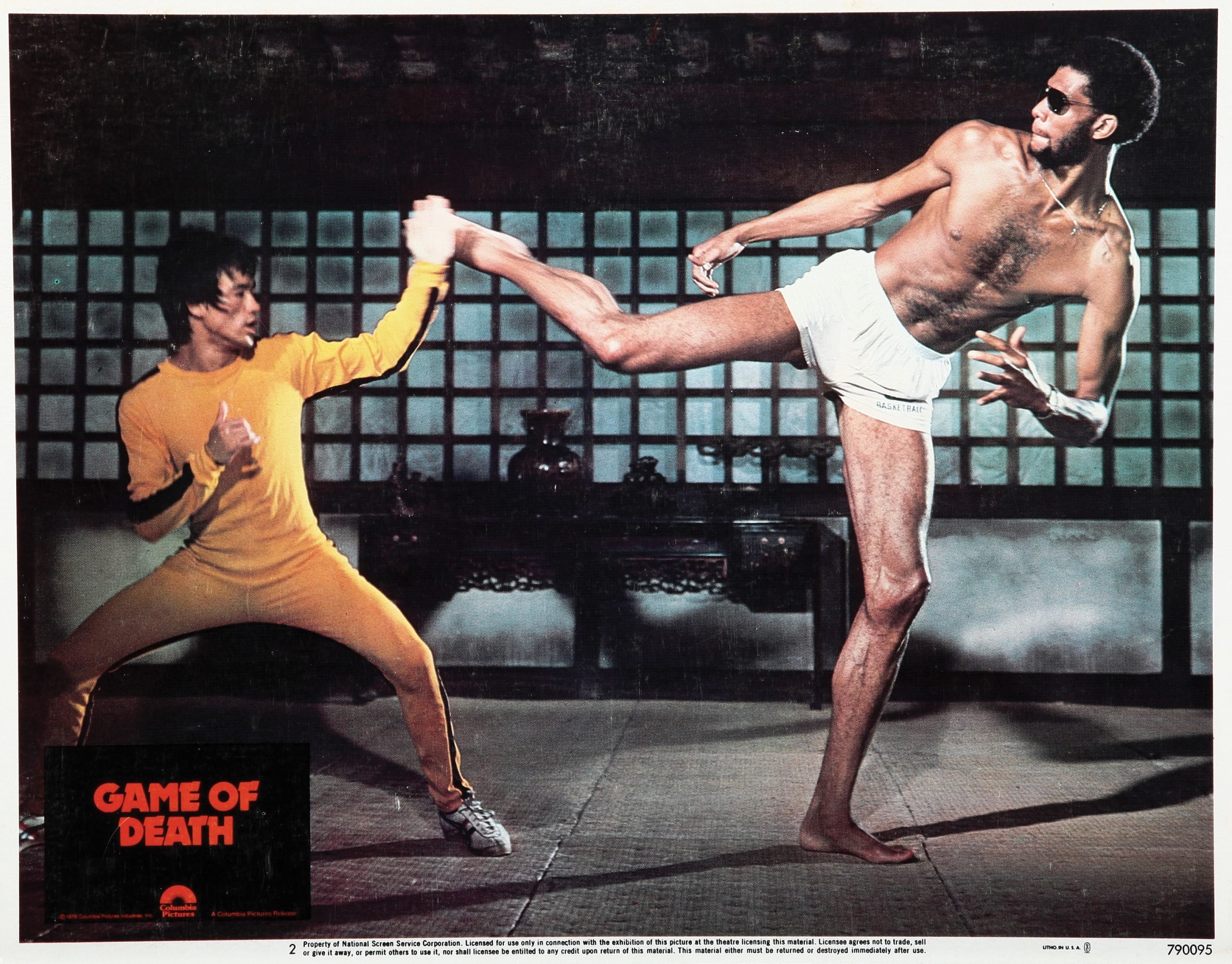

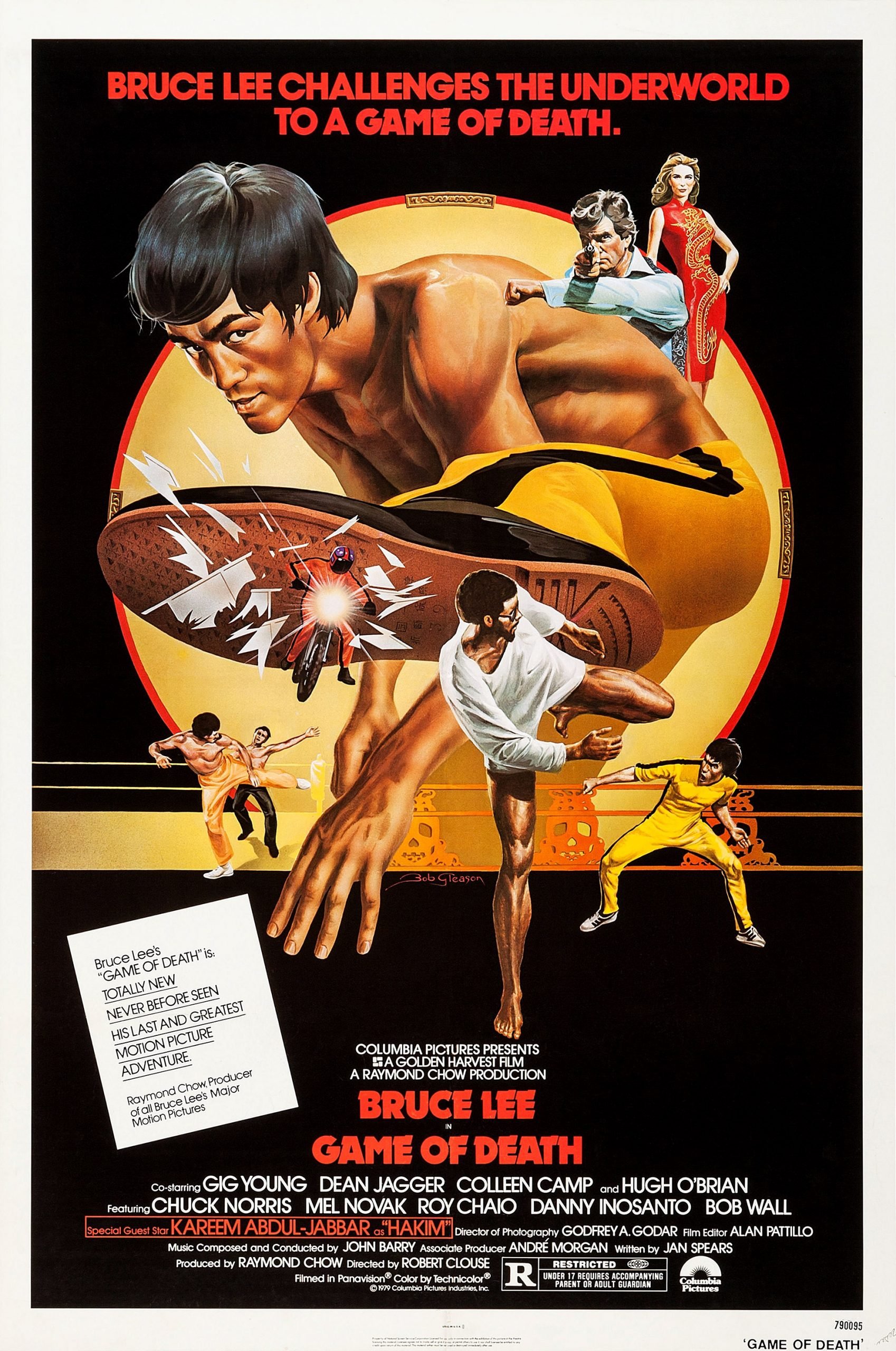

Bruce’s last, unfinished project, was ‘Game of Death,’ which they released posthumously with a new story wrapped around the footage he’d shot before his death. The sheer stupidity of the final results was pretty offensive.

MATTHEW POLLY: Every fan hates that movie. Part of it is because there was 30 minutes of actual filming that he had done, and they cut that down to seven or eight, and at the very least, they could’ve let the whole thing run as the last 30 minutes of the movie, instead of just five or six minutes. When I talked to producer Andre Morgan, their view was they were in an impossible mess. He didn’t have a script and said, “We were trying to figure out how to put this together, and it was insanity and this was the best we could do.” The one thing I can say is, looking at other Kung Fu movies from that time, Game of Death is better than some of them. It’s a really low bar, but they’re well aware of the criticism, and Raymond Chow has said through the years, “I never wanted to make the movie, but there were contracts with distributors and I felt like I had to.” When things are uncomfortable, no one wants to claim credit for them in Hollywood.

When you look at all the footage, which was featured in the documentary Warrior’s Journey, he definitely had some work to do on his screenwriting skills, but the actual fights themselves were fantastic. And so was the concept — his character fights his way up the levels of a pagoda to achieve a certain goal. I’ll tell friends about what the idea was and they’re, like, “Oh that seems kind of hackneyed.” I was like, “That’s because everybody’s copied it.” That movie was the basis of almost every single video game. Doom, you go in and you fight up levels, and that’s The Raid as well, so he caught a real archetypal idea, but he couldn’t figure out how to make it work. The story concept eluded him while he was still working on it. It eluded them when they were trying in 1978 as well.

What’s amazing is the way that the Bruce Lee phenomenon is continually refueling itself, with interest still growing after all of these years.

MATTHEW POLLY: I think that that’s due to two things. One is, there are no other iconic Asian Americans. He’s the most famous to ever exist and the second isn’t even close. Then the second is, all of these millions and millions of martial arts nerds who got into the martial arts because of him, and so for them he’s a very alive presence. That’s why I think he’s became sort of a patron saint, because I know my own feelings are I wouldn’t have gotten into the martial arts if not for him. And martial arts improved my life and changed the trajectory of it, and so he holds a special place in my heart that other famous people who I liked on screen and admire just don’t. So I think as long as his legacy lasts through Westerners studying martial arts, he will always have a place in the culture.

Please scroll down for a visual guide to Bruce Lee’s career.

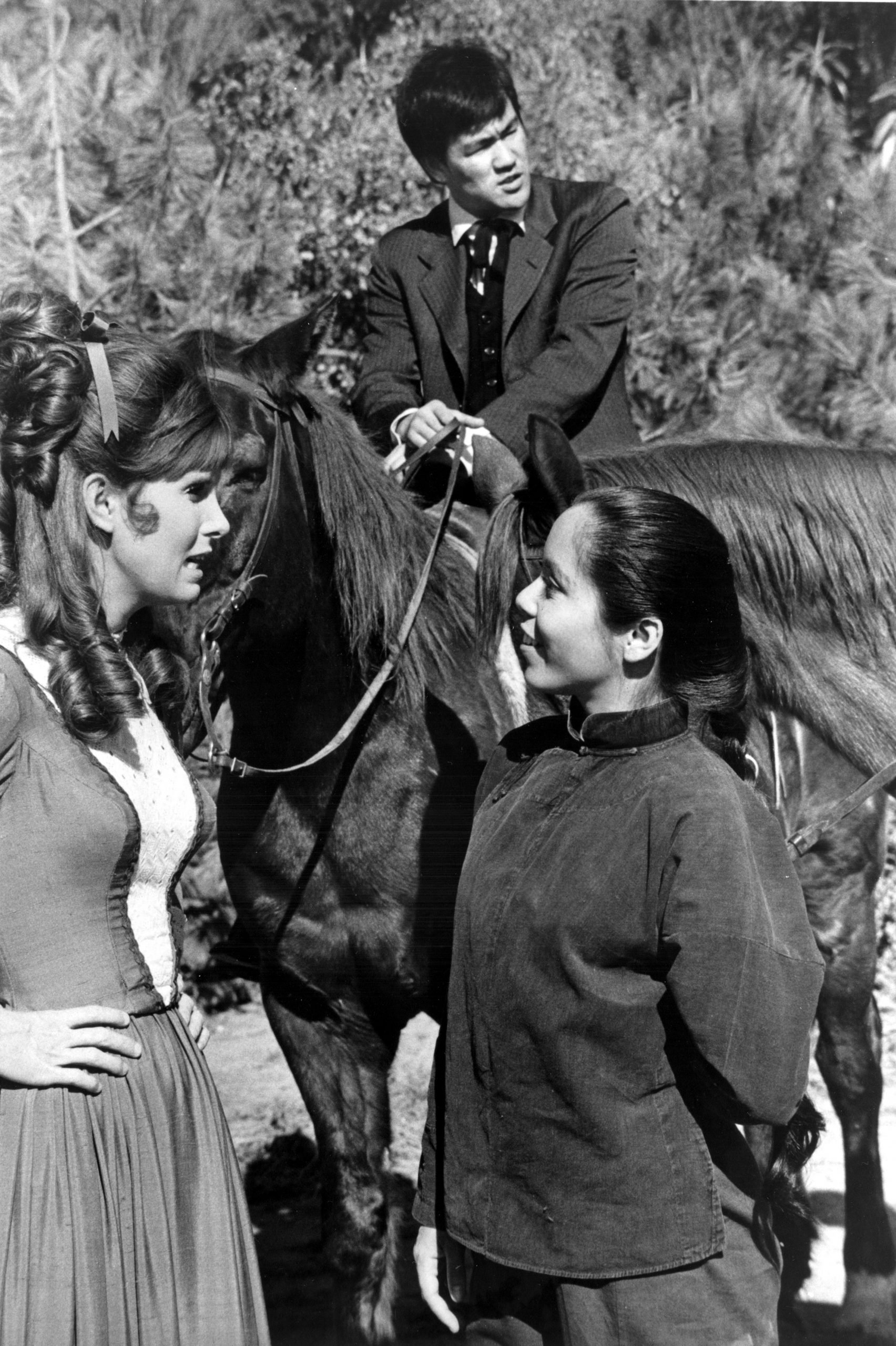

‘The Green Hornet’ (1966 to 1967 TV Series)

‘Ironside’ (1967 TV Series Guest Star)

‘Here Come the Brides’ (1969 TV Series Guest Star)

‘Marlowe’ (1969 Film)

‘Longstreet’ (1971 TV Series Recurring Role)

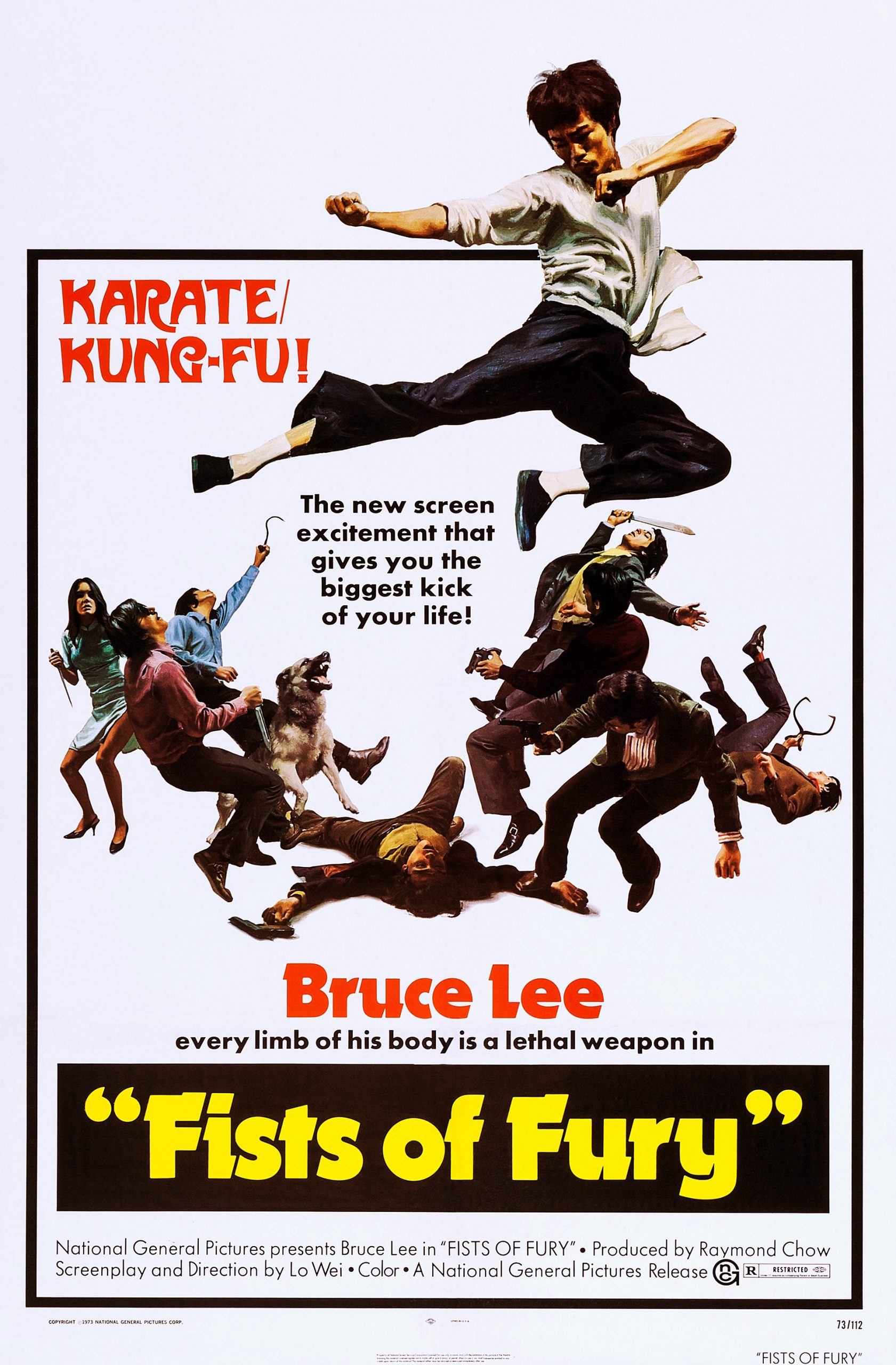

‘Fists of Fury’ (aka ‘The Big Boss’) (1971 Film)

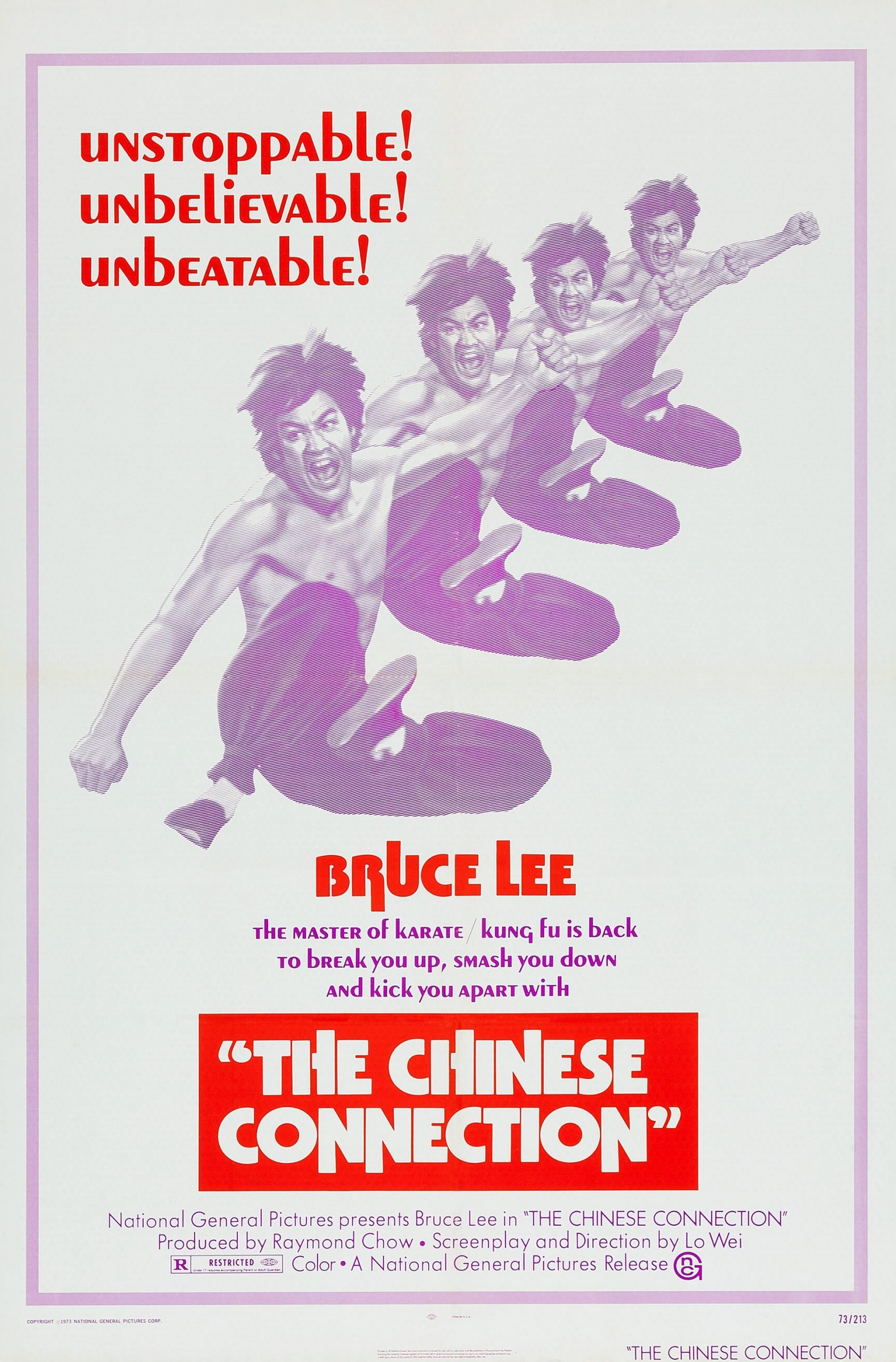

‘Fists of Fury’ (aka ‘The Chinese Connection’) (1972 Film)

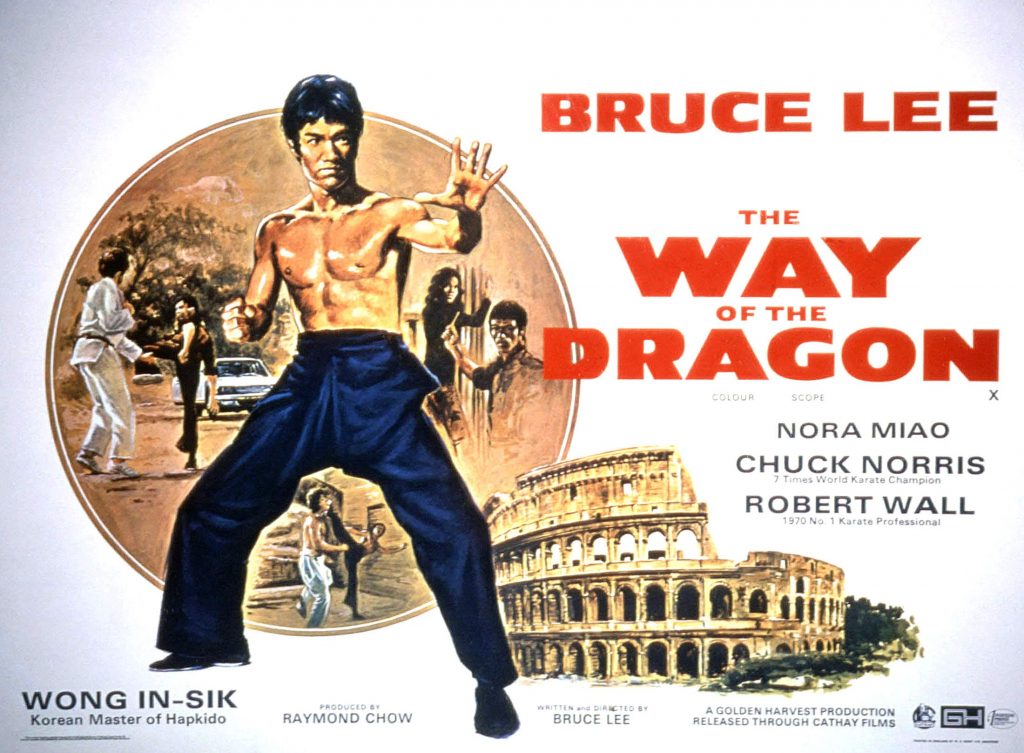

‘The Way of the Dragon’ (aka ‘Return of the Dragon’) (1972 Film)

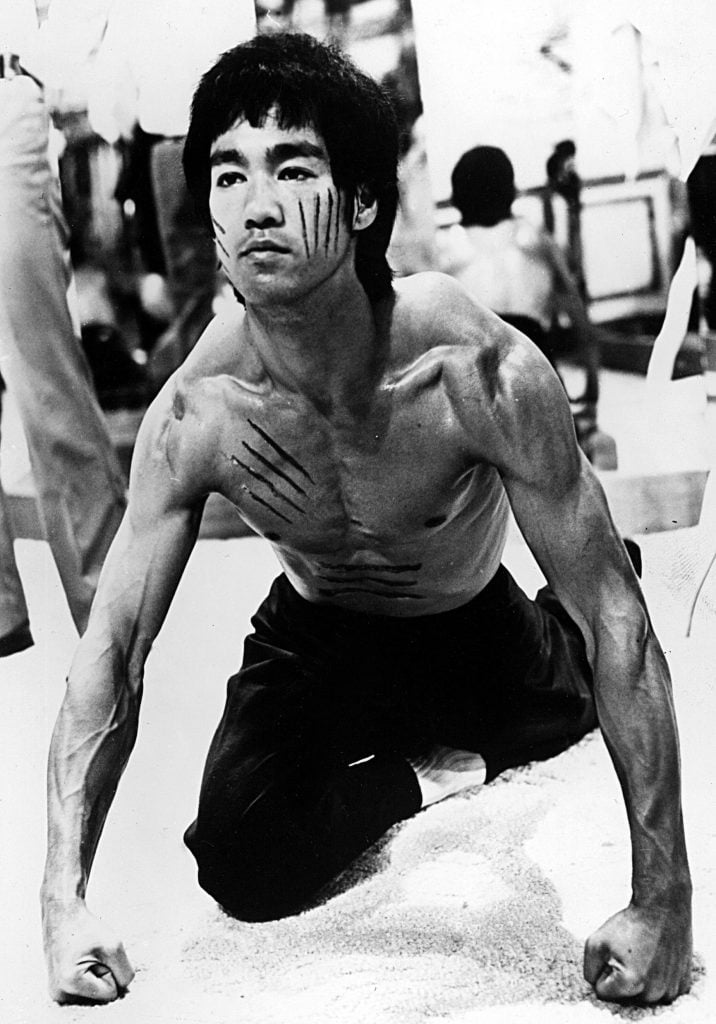

‘Enter the Dragon’ (1973 Film)

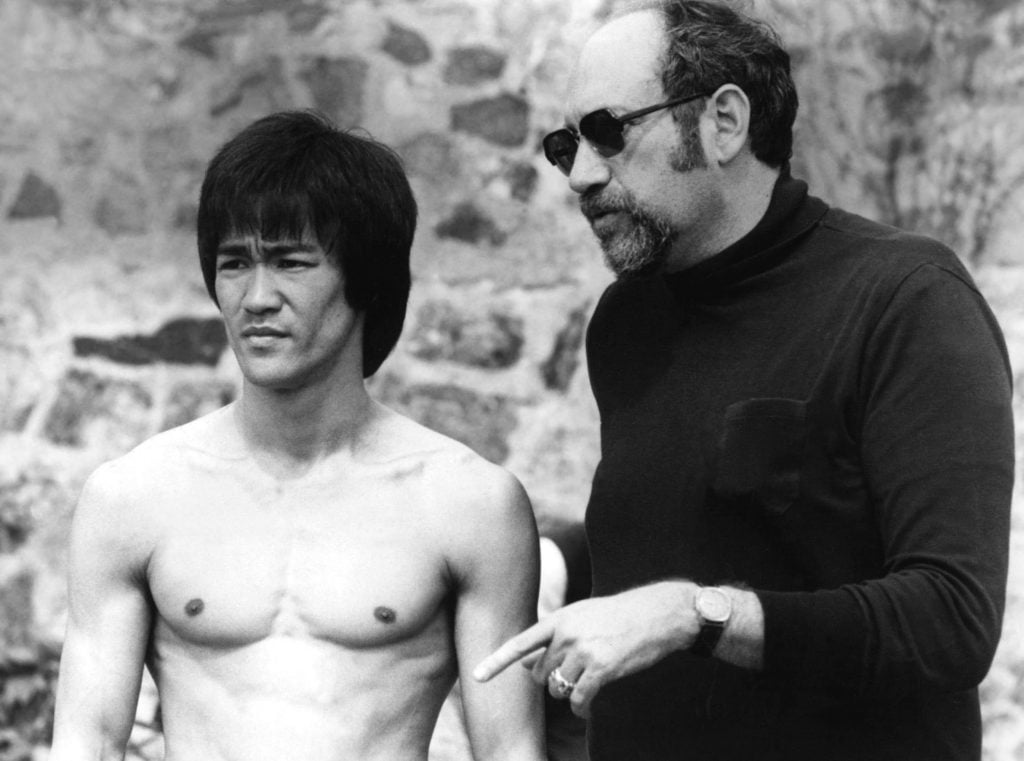

‘Game of Death’ (1978 Film)