Art is subjective. Everyone has their own preferences and dislikes. Even the King of Rock and Roll had haters, but Elvis Presley still managed to get their financial support. He even did so by embracing their overt dislike of him.

But how? As Elvis haters, wouldn’t they want to avoid anything to promote his image or fame? That’s correct; they did avoid promoting him like that. But they did not avoid vocalizing their dislike for him, wearing their disdain like a badge – literally. Colonel Tom Parker became the mastermind behind one of the mort unorthodox marketing strategies from anyone involved in a management contract.

Step 1: Set up Elvis as a brand

Elvis Presley became a surprise sensation, even to those working with him. Most particularly, Colonel Tom Parker changed his expectations for Presley as the years went on. He signed the then-rising star to a management contract in March 1956. Colonel Parker recognized Presley as the next big hit but also did not see his fame lasting for many years, only a couple.

RELATED: Elvis Presley Allegedly Phoned President Jimmy Carter ‘Totally Stoned’ Weeks Before Death

The Presley-Parker duo represented a meeting of unorthodox and successful minds, though. Reportedly, Presley harbored a secret, ultimate dream of becoming a movie star. Colonel Parker utilized merchandising and promotional strategies more common among movie icons and brands to make Elvis something of a brand himself. Both took extreme risks that yielded major financial benefits, including the success of Heartbreak Hotel and Parker’s $40,000 deal with a Beverly Hills movie merchandiser. With all the pieces aligned, it was time to really get creative.

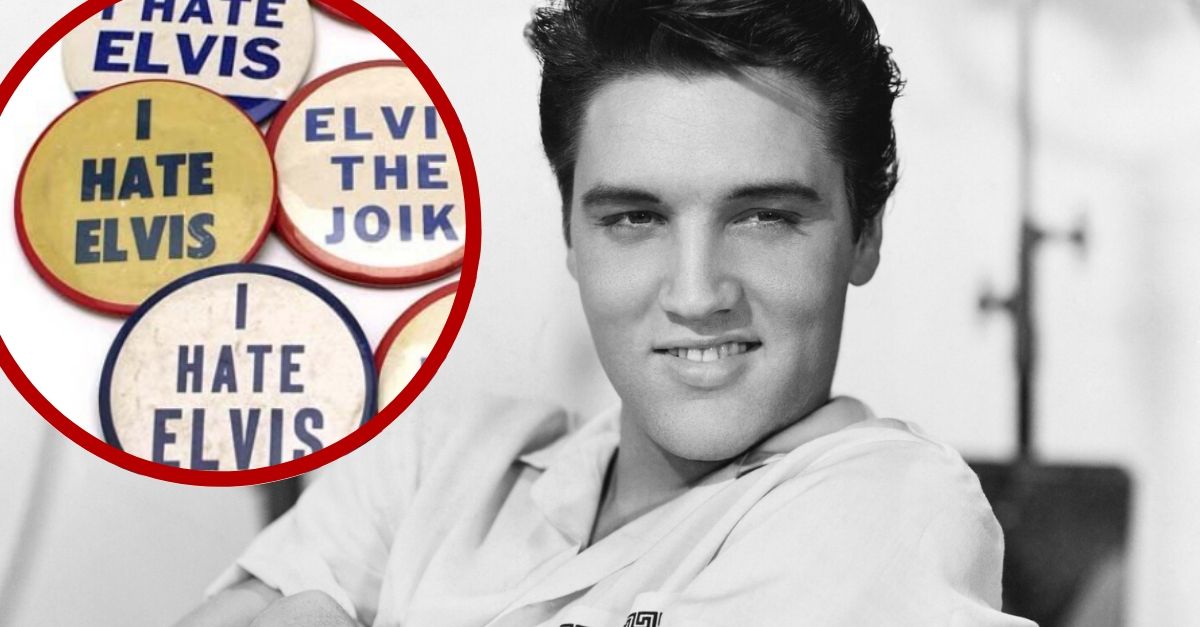

Haters declaring “I Hate Elvis” only helped Elvis

Looking around today shows plainly how divisive some artists can be. Nobody has universal love and some even have enthusiastic haters. Elvis Presley was no different. But the ingenious Colonel Parker saw a way to make money off of his detractors too. He pushed the production of “I Hate Elvis” buttons, a whole array of pins with different ways of denouncing the King and all his hip-swaying glory.

Remarkably, CBC writes, moves like these kept Elvis relevant even in his absence. His two-year stint in the army did not sweep him from the public consciousness. Parker went from an ex-carnival promoter to a founding father of modern music merchandising. Strategies like his, which called for launching extensive amounts of Elvis-themed products, permeated into the present. One man’s adaptive approach to something that had no precedented trajectory ended up setting a standard. All the while, he did so in an unusual but very effective way.