Fabray later starred in a short-lived, 1961 situation comedy on NBC — “Westinghouse Playhouse starring Nanette Fabray and Wendell Corey” — in which she played a Broadway star whose new husband, a widower living in Beverly Hills, has two children.

The series was created by Fabray’s second husband, screenwriter Ranald MacDougall. He died in 1973.

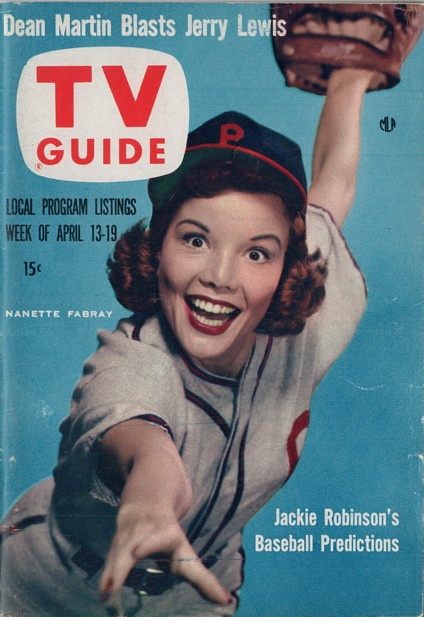

Fabray, who received a Tony nomination in 1963 for her performance in the musical comedy “Mr. President,” made numerous guest appearances on TV variety shows — as well as appearing regularly on game shows such as “Password” and “Hollywood Squares.”

She also played Mary Tyler Moore’s mother in two episodes of “The Mary Tyler Moore Show,” had a semi-regular role as Bonnie Franklin’s mother on “One Day at a Time” and played real-life niece Shelley Fabares’ mother on four episodes of “Coach.”

She also became an outspoken advocate for the hearing impaired.

Fabray, whose own undiagnosed hearing problem affected her grades in high school, was in her early 30s and appearing in a production of “Bloomer Girl” in Chicago when she found she no longer could hear the pit orchestra.

A doctor she found in the phone book predicted she’d lose her hearing in about five years.

She was diagnosed with otosclerosis, a disorder in which excessive growth in the bones of the middle ear interferes with the transmission of sound.

“If I’d known another person in the public eye who had a handicapping problem, it would have given me comfort. But I didn’t,” she told the Washington Post in 1984. “So I kept my problem to myself. My hearing kept going down.”

She said she became “so neurotically involved with my problem, so totally self-involved, so insecure,” that it destroyed her life with her first husband, David Tebet.

Fabray, who learned sign language, wore hearing aids until four operations between 1955 and 1977 restored her hearing.

Over the years, she served on the boards of the National Council on Disability, the President’s Committee on Employment of People With Disabilities and the Better Hearing Institute, among others.