A GROUP OF ARTISTS HUNCH over a massive, colorful mosaic consuming a 7,000 square-foot workshop space. Fast fingers expertly twist and spin thousands of the six-color Rubik’s Cube, then strategically place each individual cube. Piles of vinyl records, Lego bricks, crayons, 8-track tapes, and a very impressive mountain of Rubik’s Cubes clutter the Toronto home base of Cube Works, an art studio that builds massive, intricate murals out of nostalgic items.

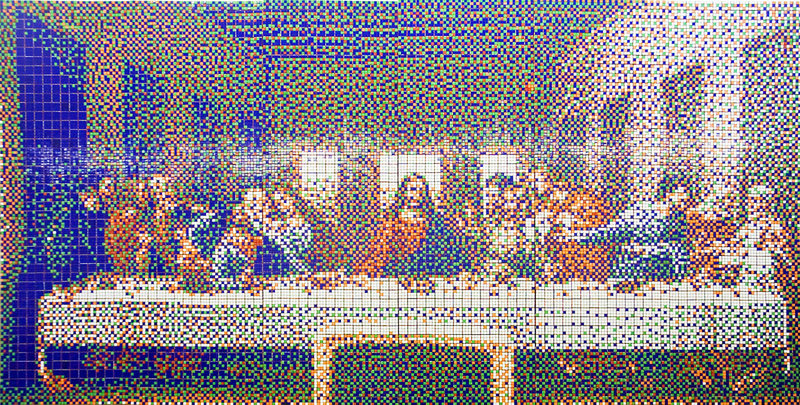

While the eight-year-old studio uses all sorts of toys as art mediums, it specializes in the Rubik’s Cube. Cube Works’ artists have recreated some of the most famous art masterpieces and iconic images, twisting each Rubik’s Cube to arrange the six colors into retro, pixelated iterations. The end result ranges from a 4,050-cube mural of Leonardo da Vinci’s “The Last Supper” to the 85,794-cube behemoth that depicts the skyline of Macau, China.

To create such large, complex art pieces, Cube Works artists follow an intricate and laborious process of image digitization and cube manipulation. First, the graphics architect creates a blueprint, a grid that maps the colors of the image. The software that pixelates the images has a bank of hundreds of colors, while the Rubik’s Cube only has six—blue, red, green, orange, yellow, and white. “When the six colors come out, it’s kind of a mess,” says Josh Chalom, creative director of Cube Works.

The graphics architect must manually change the colors of individual pixels so from a distance a mix of white, yellow, and orange, for example, will look like flesh tones. Creating the image blueprint can sometimes be the longest part of the process. A reproduction of Michelangelo’s “The Hand of God” took over 200 hours just to convert the original painting into a pixelation of six colors.

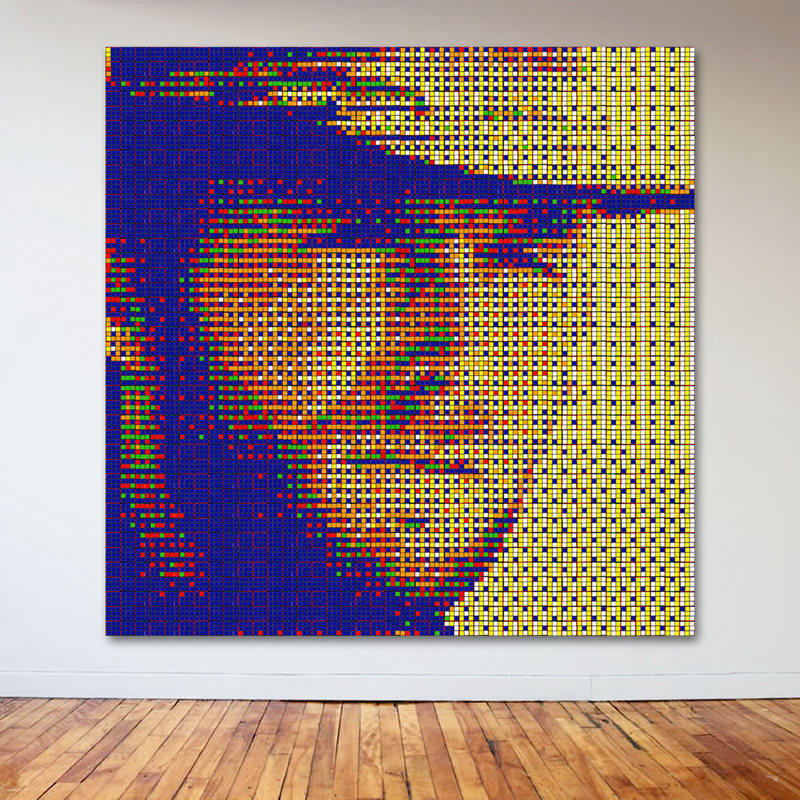

A team of lead cubers, usually one to three depending on the size of the piece, will then twist and turn each cube with speedy hands to match the color pattern on the grid. These Rubik’s Cube masters can assemble between 700 to 1,000 cubes a day, and most of them are able to solve the cube in under 15 seconds. After the cubes have been properly matched to the blueprint, they are fastened to large panels, each holding roughly 150 to 180 cubes.

An average-sized portrait takes about a day or two to complete, while a large mural like the Macau skyline can require up to two weeks. When Cube Works unveiled the first pieces, people thought that the artists simply rearranged the stickers.

“We don’t use the original Rubik’s Cube because the stickers tend to fade and not last as long,” says Chalom. Instead, the studio orders a completely plastic version of the cube, which has tiles that stay vibrant longer and are a lot more durable. They can even withstand humid environments—Cube Works has built a piece for an indoor pool.

Cube Works has since expanded beyond the Rubik’s Cube, and are now commissioned to work with broken vinyl, bottle caps, Legos, guitar picks, and Crayola crayons—which Chalom says is refreshing after looking at six colors all the time. Currently, Chalom and his artists are working on a giant crayon mural comprised of many smaller art pieces that can eventually be broken up and sold to charity. He is also trying to find the appropriate space for a very ambitious ceiling suspension of the whole Sistine Chapel, a project he estimates will require 250,000 Rubik’s Cubes.