5. Hiram Bingham III

The man credited with the discovery of the 15th century Inca citadel Machu Picchu, situated in the Peruvian mountains, Hiram Bingham III, was an American academic, explorer and politician. Even though he wasn’t a trained archeologist, his passion for adventure led him on a search for the long-lost city.

Machu Picchu wasn’t exactly discovered by Bingham but was rather made known to the wider public by him. The American explorer had employed indigenous guides who already knew about the location of the citadel, but their attitude towards it differed from that of Bingham’s who, along with the rest of the western world, took great interest in it for many reasons.

Yale University in 1911 sponsored his first expedition, as he was then a professor of Latin American History and well acquainted with the customs of the local population. Since the expedition was a success, he was granted funds to return and continue his exploration.

In his later life, Bingham went into politics, becoming a Governor of Connecticut and a member of the US Senate.

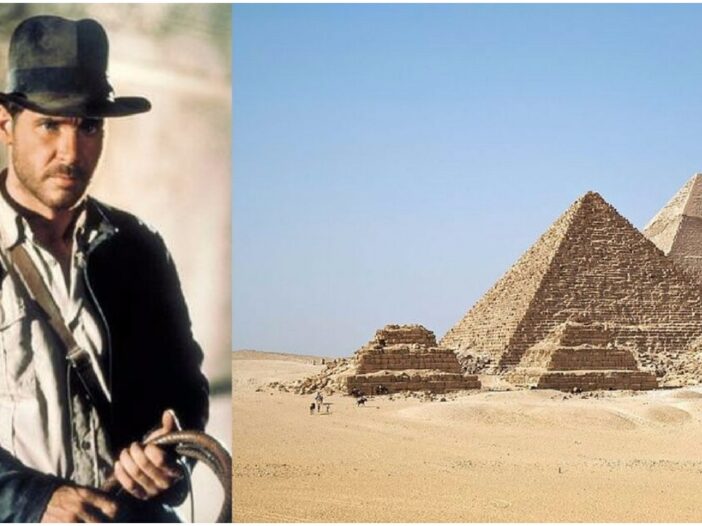

6. Giovanni Battista Belzoni

A rather interesting addition to this list is the 19th-century circus strongman from Italy, Giovanni Battista Belzoni. Together with his English wife, he performed all over Europe, exhibiting his strength as part of a circus attraction.

Besides his physical traits, Belzoni had a passion for developing hydraulic engines. It was this passion that led him to Egypt as he hoped to strike a sale of his machines to the Egyptian ruler, Muhammad Ali of Egypt. Unfortunately, Ali lost interest in the hydraulic engines, and Belzoni was stranded in the land of the pharaohs.

His wife went to the British consulate in Cairo, where she was employed together with her husband to conduct archeological excavations. Keep in mind that in the 19th century, archeology was more a tomb raiding business than a science.

The accidental archaeologist made excavations at the Ramesseum at Thebes, discovered and opened the tomb of Seti I, and became the first modern person to enter the pyramid of Khafre at Giza. Even though he was considered a “Pillager,” the British Museum once noted that “he was no worse than his contemporaries.”