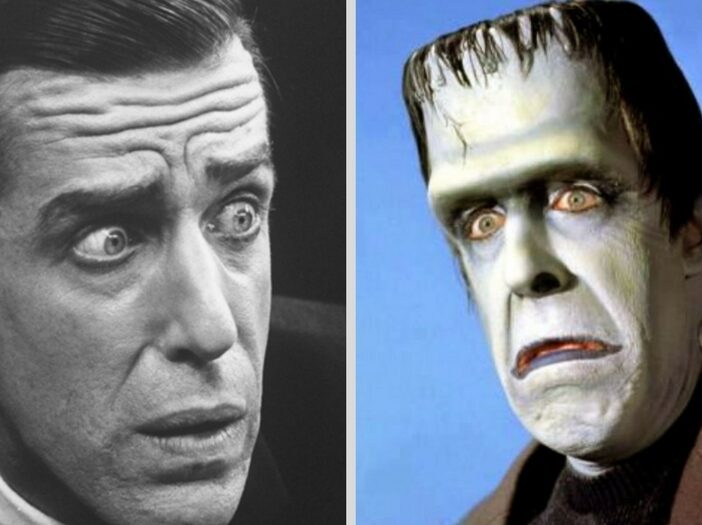

After that, offers were infrequent and he became an advertising copywriter, acting when roles came along. (One of those was a supporting part in On the Waterfront with Marlon Brando.) Persistence paid off; his stage appearances led to a television offer. He became the star of Car 54, Where Are You? in which he played one-half of a pair of mismatched New York City cops in the Bronx. After that show ended in 1963, Gwynne landed the role that would define him for the rest of his life: Herman Munster on The Munsters. A review in the New York Times declared that “there is not the slightest question that Mr. Gwynne superbly made up as Frankenstein, is the whole show. His shy and modest demeanor as one who yearns only to be a good neighbor sets the tone for all the other doings…”

That superb makeup included a face of paint, neck bolts, and garish forehead scar. According to gossip columnist Hedda Hopper, “It takes him 2.5 hours to put on that monstrous make-up which he does three or four days a week. He’s too exhausted after that to make many guest appearances on other shows.” A buddy told theCrimson he suspected it was extensive costuming that in later years made it difficult for Gwynne to turn his head.

As his acting career took off, Gwynne continued to make art, sculpting, and painting. He published his first children’s book, Best in Show, (about a girl who enters her dog in a contest where all the dogs look like their owners) in 1958. It would be republished several years later as Easy to See Why, the title by which it is most commonly known. Gwynne’s career as an author and illustrator began in earnest in the 1970s, during which he published several books included The King Who Rained and A Chocolate Moose for Dinner. Their pages offered up statements such as “Daddy says there are forks in the road.”, and an illustration of rolling hills overlaid with massive forks upon which the traffic drives. Gwynne’s illustrations are richly detailed and saturated in color.

“I love making puns,” Gwynne told a reporter for the Knight-Ridder Tribune News Service in 1989. He supported this statement by showing her a brass sculpture of a banana he had made, which rang like a bell when he shook it. “Banana Peal,” he said “laughing his great, deep laugh.” During the same visit, he showed the writer another object of his—a clear, lucite Sherman tank with a model of a fish inside; a “Fish Tank”. The article was written on occasion of his first art show, “Drawn and Quartered: Wordplays in Oils, Bronze, and Others” at a gallery in New York.

Click “NEXT” for more pun books! (No Pun intended!)